Longitudinal Trends: Ideological Diversity In Universities v. Surrounding Communities

Colleges and the communities they are embedded in are both becoming more ideologically homogenous. Why?

In a recent book, Land Grant Universities for the Future, Stephen Gavazzi and Gordon Gee analyze polling data from land grant universities and their host communities and find that institutions of higher learning tend to be “islands of blue” which mirror state capitals and major urban areas, inside “vast seas of red” – i.e. the surrounding towns and countryside (which tend to lean decisively Republican).

Jeffrey Adam Sachs advances a similar argument in a recent Heterodox Academy post: liberal arts colleges and research universities tend to hail from states that lean much farther left than the rest of the country:

“The average liberal arts college is located in a state with a PVI score of D+6.4 (meaning that the Democratic Party vote share there was 6.4 percentage points greater than in nation as a whole) and in a congressional district of D+6. Even more striking, the average research university is in a state with a PVI score of D+4.1 and in a congressional district of D+16.6. In other words, the leading institutions in higher education – especially those that train future faculty – are located in places far more Democratic (and probably far more liberal) than the nation as a whole.”

That universities tend to be embedded in starkly liberal communities, he argued, may help explain the political imbalance within institutions of higher learning:

“Graduate students and professors do not spend all of their time in the library or laboratory, though it can often feel that way. They are also members of the larger community. They are neighbors, worshippers, and volunteers. They join the PTA, watch the local news, and use local services. It seems implausible to think that they are not affected, ideologically or in terms of partisan identity, by these interactions.

In particular, two potential mechanisms may be at work: 1) exit, in which conservative or Republican graduate students/faculty feel so out of place in heavily liberal or Democratic communities that they choose to either avoid or move away from the country’s top colleges and universities; and 2) conversion, in which graduate students/faculty who would otherwise be conservative or Republican shift their political identities leftward due to community socialization… Of course, it is also possible that the causal path runs in the opposite direction and a community’s Democratic PVI is due to the liberal lean of its college or university. However, this is extremely unlikely.”

In a subsequent Twitter thread, he expanded on this argument, highlighting how these disparities may also explain the partisan imbalance in commencement speakers: 65% of political figures invited to give these addresses seem to be Democrats. Yet about a fifth of all these invited speakers are local figures (representing a jurisdiction that extends ten miles or less from the university) – and it turns out that officials representing these areas are roughly three times as likely to be Democrats rather than Republicans. For liberal arts schools and research universities in particular, even their federal Congress people and state governors are far more likely to be “blue” than “red” (considering the PVI score of those states).

30 Year Trends

Reading Sachs’ essay, my immediate thought was that if there is indeed some kind of casual relationship between the ideological imbalance in universities and those of the communities they are embedded in, we would expect the correlations Sachs highlights between “community and campus” to persist longitudinally.

So I tested that idea:

Liberal arts colleges and research universities, especially elite ones, are heavily concentrated within the “Northeast Corridor” (running from Boston through Washington D.C.) and along the West Coast. As Sam Abrams has demonstrated, these are the very regions where the academic ideological imbalance is most pronounced today (e.g. here, here).

These schools produce a shockingly high share of all full-time faculty nationwide, play a disproportionate role in shaping public attitudes about universities and students, and set policies and best-practices that other schools strive to emulate. In other words, what happens in these regions, and for these institutions, tends to have important ramifications for the academy overall.

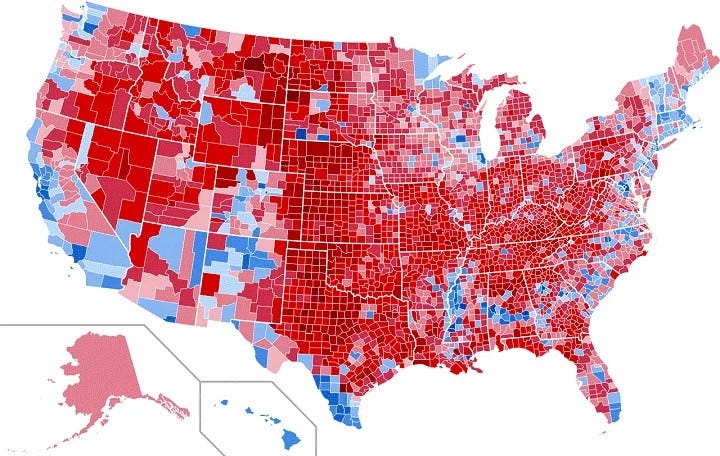

In the 80’s and 90’s, the districts these schools are located in were far more competitive for Republicans than they are today. For instance, here is a political heatmap of the 1988 general election vote shares:

Now compare that to 2016:

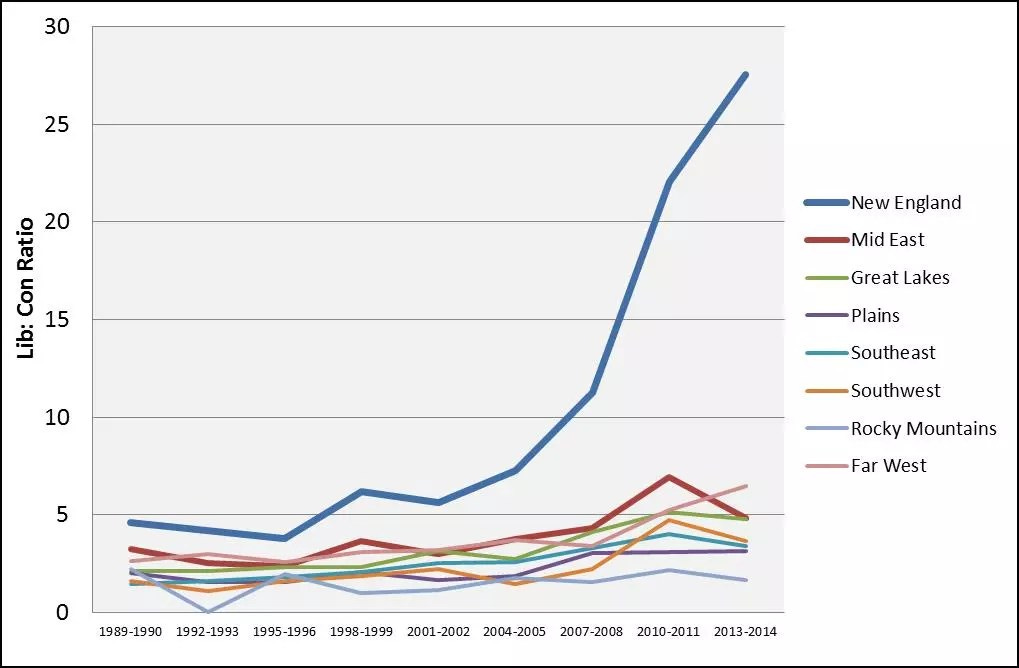

We see a dramatic blue shift in areas where liberal arts colleges and research universities are concentrated (West Coast, Northeast Corridor). And just as those regions were far more Republican in 1988, university faculty were also far more politically diverse then, as compared to now:

As the Northeast Corridor and West Coast has become increasingly “blue” we have gone from roughly a 2:1 ratio of liberals to conservatives among faculty in the late 80’s, to a roughly 5:1 ratio today. Indeed, the ideological shift was especially pronounced among faculty in New England and the West Coast:

In short, there does seem to be a longitudinal correlation between the lean of faculty at universities and the lean of their surrounding communities. However, there is still the outstanding question of the causal direction of the relationship: is it the case that universities are being pulled to the left by the communities and regions they are embedded in? Or might it be that the growing political imbalance at universities is pushing these communities leftward instead? Or is it some kind of feedback loop, with each pulling the other leftward in a dialectical pattern? Or is some other force at work simultaneously driving both universities and their communities “left”?

Sachs believes the former is more likely the case. It’s worth dwelling a moment on what it means if he’s right.

The Revenge of Geography

Sachs concludes his essay as follows:

“For those concerned by the lack of academic viewpoint diversity, these findings represent both good and bad news. On the one hand, they suggest that the academy itself may not be entirely responsible for its own political imbalance. Discrimination and self-censorship on campus could indeed be important factors, but the academy may be doing less wrong than is commonly thought. On the other hand, this would mean that the problem may also be more intractable than is commonly thought. To the extent that the lack of viewpoint diversity is due to the political lean of the larger community, there is that much less that organizations like Heterodox Academy can do about it.”

Reading these lines, I had two thoughts:

First, if it is the case that these trends are being driven primarily by socioeconomic and cultural forces that play out across geographical lines, the work of correcting these imbalances would become even more important. It wouldn’t just be a matter of rectifying the practical problems that arise out of insufficient viewpoint diversity, there would also be the moral issue that large segments of the population are being systematically excluded from higher education and the opportunities it provides — with entire regions of the country being left behind. Everyone, perhaps especially those on the left, should be concerned about addressing such an injustice.

Yet, at the same time, it would also matter a lot less how faculty, staff or students felt about these issues. This seemed to be what Sachs was driving at:

Heterodox Academy could expand dramatically. Our members could help ensure the processes of hiring, promotion, admissions, peer review, etc. are as fair and open as possible; we could help make campus culture more inclusive and constructive. Yet while these pursuits may be worthy for their own sake — to improve the quality and impact of research and teaching as much as possible given the diversity that currently exists – the pipeline problem would likely remain, or even deepen. Universities may become more hospitable to conservative, religious and other underrepresented perspectives, but their numbers may continue to dwindle nonetheless as a result of broader social dynamics.

For those eager to actually increase levels of political diversity within institutions of higher learning, these observations could induce despair or resignation… but they shouldn’t. As Robert Kaplan put it:

“Geography in many places tells many stories… There is such a thing as human agency, the decisions of men, our responsibility before history. Vast, impersonal forces can be overcome, but first by realizing how formidable they are.”

If Sachs is right about the causal dynamics underlying the correlation, then meaningfully addressing the ideological imbalance in the academy would require a sober, patient and disciplined campaign – and likely a totally different approach. The primary goal would not be to win hearts and minds of those already in the academy about the need for viewpoint diversity, etcetera. Instead the focus would be on extending access and opportunity to a broader swath of the population. For instance, university leadership could commit to enhancing financial support, benefits, and flexibility for students. This will help improve the perceived feasibility of higher ed, and help improve retention for those who are accepted — particularly among students who also work, have families or other pressing needs/ commitments (increasing faculty compensation could also help). However, given the financial pressures facing many institutions of higher learning, paying for this would require winning over policymakers and the general public — many of whom currently favor defunding institutions of higher learning — rather than focusing so intensely on influencing the attitudes of academic faculty or students.

Again, it’d still be important for people already *in* the academy to embrace a broader range of perspectives for the sake of their own learning, research and teaching — this has always been HxA’s primary goal. However, if Sachs is right, these changes to university culture, on their own, likely wouldn’t meaningfully affect levels of representation.

But of course, the million-dollar question remains: is Sachs right?