Contextualizing the 2024 Election: It's the (Knowledge) Economy, Stupid

The urban v. rural divide, the gender divide and the diploma divide are all proxies for the most fundamental division in contemporary U.S. politics

Note: I published the essay that follows about a year ago. It draws heavily on themes from both my newly released book (We Have Never Been Woke) and my next book (details coming soon). As you’ll see, the essay nicely explains the 2024 electoral results.1

Rather than viewing the gender divide, the ethnic shifts, the education divide, etc. as separate phenomena, it’s more insightful to understand them as facets of a more fundamental schism in American society. And many other societies worldwide. Namely: a divide between “symbolic capitalists” and those who feel unrepresented in our social order.2

I fear that, as happened in 2016, rather than really taking the points of this essay to heart, the impulse in many symbolic capitalists spaces will be to try to pathologize *the voters* rather than the Democratic party, its candidates, its messaging, or its platform and priorities. So I’m hoping to inoculate readers against those types of asinine takes by presenting an alternative — and analytically powerful —way of understanding what’s going on.

For editors/ journalists interested in essays or interviews about any of this stuff, hit me up ASAP. My bandwidth is tight because of the book tour, but I'll make time for the right pitch.

The biggest divide in American politics at present is not along the lines of socioeconomic status (SES), nor educational attainment, nor type (urban, suburban, small town, rural), nor gender — nor is it tied to “identity politics,” “populism,” or the “crisis of expertise” — although these factors all serve as important proxies for the distinction that matters most. The key schism that lies at the heart of dysfunction within the Democratic Party and the U.S. political system more broadly seems to be between professionals associated with ‘knowledge economy’ industries and those who feel themselves to be the ‘losers’ in the knowledge economy – including growing numbers of working class and non-white voters.

Two decades ago, sociologists Manza and Brooks observed, “professionals have moved from being the most Republican class in the 1950s, to the second most Democratic class by the late 1980s and the most Democratic class in 1996.” The consolidation they noted at the turn of the century is even more pronounced today. And as these professionals have been consolidated into the Democratic Party, they’ve grown increasingly progressive, particularly on ‘cultural’ issues (sexuality, race, gender, environmentalism), and especially relative to blue-collar workers.

FEC campaign contribution data provides stark insights into how firmly knowledge economy professionals have aligned themselves with the Democratic Party in recent cycles. In 2016, roughly 9 out of 10 political donations from those who work as activists, or in the arts, academia, and journalism were given to Democrats. Similarly, Democrats received around 80% of donations from workers involved in research, entertainment, non-profits and science. They also received more than two-thirds of donations from those in IT, law, engineering, public relations, or civil service. Among industries that skewed Democratic, the party’s highest total contributions came from lawyers/ law firms, environmental PACs, non-profits, the education sector, the entertainment sector, consulting and publishing.

Similar patterns held in 2020: the occupations and employers with the most workers who donated to the Biden/ Harris campaign included teachers, educators and professors, lawyers, medical and psychiatric professionals, people who work in advertising, communications and entertainment, consultants, HR professionals and administrators, architects and designers, IT specialists and engineers. Industries that provided the highest total contributions to the Democrats included securities/ investments, education, lawyers/ law firms, health professionals, non-profits, electronics companies, business services, entertainment and civil servants. Geographically speaking, Democratic votes in 2020 were tightly clustered in major cities and college towns where knowledge economy professionals live and work — and outside those zones, it was largely a sea of ‘red.’

The alignment of knowledge economy professionals with the Democratic Party has also shifted the socioeconomic composition of the Democratic base. To give some perspective of how much has changed: in 1993, the richest 20 percent of congressional districts were represented by Republicans over Democrats at a ratio of less than 2 to 1. Today, they tilt Democrat by nearly 5:1. The socioeconomic profiles of Democratic primary voters have shifted significantly as well. Counties with higher concentrations of lower and working class Americans are today a much smaller portion of Democratic primary voters than they were in 2008, while counties with large concentrations of affluent households comprise an ever-growing share. This has important consequences for the types of candidates that succeed in primary elections, the language those candidates use, the issues they center, what the party platform ends up looking like and, ultimately, who is drawn to the party and their candidates in national elections (and who is alienated therefrom).

The increasing dominance of knowledge economy professionals over the Democratic Party has had a profound impact on the contemporary U.S. political landscape:

First and foremost, it has contributed to a growing disconnect between the economic priorities of the party relative to most others in the U.S., and especially as compared to working class Americans. This is because, as sociologist Shamus Khan has shown, the economics of elites tend to operate ‘counter-cyclically’ to the rest of society. Developments that tend to be good for elites are often bad for everyone else, and vice-versa.

As an example, professionals tend to be far more supportive of immigration, globalization, automation and AI than most Americans because they make our lives more convenient and significantly lower the costs of the premium goods and services we are inclined towards. That is, those in the knowledge professions primarily see upsides with respect to these phenomena because our lifestyles and livelihoods are much less at risk (we instead capture a disproportionate share of any resultant GDP increases), and because our culture and values are being affirmed rather than threatened thereby (e.g. our embrace of demographic diversity, cultural cosmopolitanism, scientific progress). Others experience these developments quite differently.

Likewise, most in the U.S. skew ‘operationally’ left (i.e. favoring robust social safety nets, government benefits and infrastructure investment via progressive taxation) but trend more conservative on culture and symbolism. For instance, they tend to support patriotism, religiosity, national security and public order. Although they are sympathetic to many left-aligned policies, they tend to prefer policies and messages that are universal and appeal to superordinate identities over ones oriented around specific identity groups (e.g. LGBTQ people, women, Hispanics, Muslims). They tend to be alienated by political correctness and prefer candidates and messages that are direct, concise and plainspoken. Knowledge economy professionals tend to have preferences that are diametrically opposed to those of most other Americans, especially working-class voters.

With respect to values, we skew culturally and symbolically ‘left’ but favor free markets. As statistician Andrew Gelman showed, elites in the Republican Party tend to be significantly more liberal culturally and symbolically than the rest of the GOP, yet more dogmatic about free markets. Meanwhile, Democratic-aligned elites tend to be significantly more ‘left’ on cultural and symbolic issues than most Democrats, but tend to be much warmer on markets. The primary difference between Democratic and Republican elites seems to lie in how they rank free markets relative to cultural liberalism: those who prioritize the former have tended to align with the Republicans; those who prioritize the latter have consistently aligned with the Democrats (hence, Republican elites tend to more economically and culturally ‘right’ relative to Democratic elites, while Democratic elites tend to be more economically and culturally ‘left’ relative to GOP elites. But across the board, elites in the parties tend to be more economically ‘right’ and culturally ‘left’ relative to their respective party bases).

To the extent that highly educated people support left-aligned economic policies, they tend to prioritize redistribution (taxes, transfers), whereas most other voters prefer predistribution to address inequality (e.g. higher pay, better benefits, more robust job protections so less needs to be reallocated in the first place).

Critically, although knowledge economy professionals tend to skew more ‘operationally right’ than most, they often have inaccurate understandings of their own preferences. Perhaps counterintuitively, highly-educated Americans tend to be less aware of our own socio-political preferences than most others in society. Typically, we describe ourselves as more left-wing than we actually seem to be. Studies consistently find that relatively affluent, highly-educated and cognitively sophisticated voters tend to gravitate towards a marriage of cultural liberalism and economic conservativism. However, we regularly understand ourselves as down-the-line leftists. As economist James Rockey put it, “How does education affect ideology? It would seem that the better educated, if anything, are less accurate in how they perceive their ideology. Higher levels of education are associated with being less likely to believe oneself to be right-wing, whilst simultaneously associated with being in favour of increased inequality.”

Many of us support ostensibly ‘radical’ socioeconomic policies, but in a way that prevents even modest reforms. For instance, knowledge economy professionals tend to be much more critical of capitalism in principle than many other Americans. They tend to support ‘the revolution’ in the abstract, but because revolution does not appear to be in the offing anytime soon (certainly not a leftist revolution), they largely carry on day-to-day in much the same fashion as their liberal peers. If anything, under the auspices of claims like ‘there is no ethical consumption under capitalism’ leftist professionals may show even less regard for making practical changes in their own lives, institutions and communities to advance their espoused social justice goals. Individual sacrifices or changes, it is commonly argued, are futile; nothing shy of systemic change is worth aspiring towards.

Or consider Occupy Wall Street. Although professionals love to romanticize Occupy as a solidaristic class-oriented movement, in reality, it was anything but. In fact, the Manichean framing of the Occupy movement helped obscure important class differences and the actual causes of social stratification. As David Autor aptly put it, “the singular focus of the public debate on the ‘top 1 percent’ of households overlooks the component of earnings inequality that is arguably most consequential for the ‘other 99 percent’ of citizens: the dramatic growth in the wage premium associated with higher education and cognitive ability.” That is, precisely what Occupy helped us avoid talking about is how knowledge economy professions and their employment practices are some of the main drivers of contemporary inequality, and how people like us are the primary ‘winners’ in this arrangement.

Richard Reeves powerfully argued, “The rhetoric of ‘We are the 99 percent’ has in fact been dangerously self-serving, allowing people with healthy six-figure incomes to convince themselves that they are somehow in the same economic boat as ordinary Americans, and that it is just the so-called super rich who are to blame for inequality.”

As Reeves’ research amply shows, the declines in social mobility and rising inequality cannot be well-explained or addressed by simply focusing on the ‘1 Percent.’ Yet that is precisely what many knowledge economy professionals attempted to do via Occupy: deflect blame onto others using class-based rhetoric. And rather than focusing on concrete policies to rectify the inequalities they condemned, the Occupy Movement’s approach to social change was intensely academic and, in the name of ‘inclusivity,’ was outright hostile to politics per se. Rather than advocating for concrete policies that could tangibly assist the marginalized and disadvantaged in society, or developing some actionable platform that could help promote broad-based prosperity, the movement was primarily focused on villainizing those above knowledge economy professionals on the socioeconomic ladder.

Contrary to depictions of Occupy as a broad-based movement, knowledge economy professionals were its primary base. For instance, despite the diversity of the city, participants of Occupy demonstrations in New York were overwhelmingly non-Hispanic white. They were near-uniformly liberal in their political orientations. They were also relatively affluent: roughly three quarters (72 percent) of participants came from households above the 2011 New York City median. A plurality came from households that brought in over $100k per year. 76 percent of participants had a BA degree or higher, and a majority of the rest were currently enrolled in college. Those who had jobs hailed were overwhelmingly knowledge economy professionals. Only about a quarter of employed participants had blue collar, retail or service jobs. Across the rest of the country, the picture was basically the same. Occupy protests were concentrated largely in knowledge economy hubs, and there were low rates of participation across the board for those who were not college-educated white and/or liberal — perhaps in part because the operation of the protests themselves was incredibly niche and unappealing to most ‘normies.’ As Catherine Liu aptly described it:

“The highly educated members of Occupy fetishized the procedural regulation and management of discussion to reach consensus about all collective decisions. Daily meetings or General Assemblies were managed according to a technique called the progressive stack. Its fanatical commitment to proceduralism and administrative strategy suppressed real discussion of priorities or politics and ended up promoting only the integrity of the progressive stack itself. Protecting the stack became more important than formulating political demands that might have resonated with hundreds of millions of Americans whose lives were being directly destroyed by finance capital. PMC/ New Left ideas about mass movements dominated Occupy’s dreams of politics and limited the effectiveness of its activism. Demographically and politically, Occupy was squarely a PMC elite formation.”

In other words, although knowledge economy professionals often pay lip-service to cross-class solidarity, we often conceptualize class-based politics in ways that are antithetical to the priorities and values of the lower-income people we paint ourselves as champions of.

Similar patterns are apparent in many other issue domains. For instance, knowledge economy professionals tend to be significantly to the ‘left’ on issues related to race than most non-whites, and articulate approaches to race that most non-whites find unappealing. Across the board, we often make strong claims on behalf of various historically marginalized and disadvantaged groups although our views are not particularly representative of those we purport to represent.

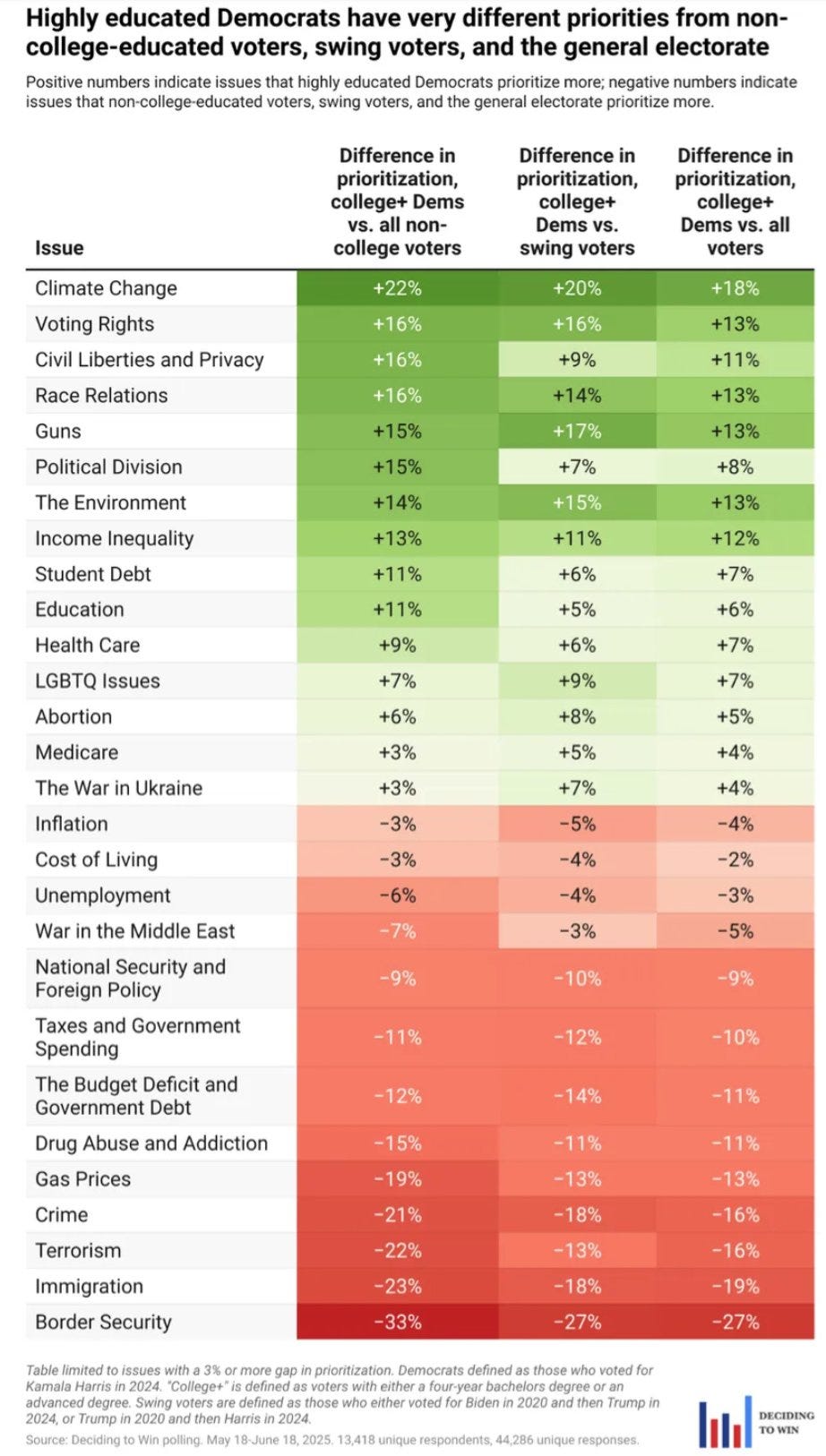

In terms of broad issue areas, a recent study found that highly-educated Democrats vary systematically from swing voters and less educated Americans (to include the rest of the Democratic base). They were far more likely to prioritize climate change, race and gender issues, democracy per se, education (including and especially student debt), and health care issues. However, they were markedly less concerned than most about crime, war, immigration, jobs, cost of living, substance abuse, and government fiscal issues.

Due to the growing divergence between us and everyone else, as the Democratic Party has drawn itself closer to knowledge economy professionals, it has grown increasingly divorced from the values, concerns and priorities of most other Americans. As knowledge economy professionals have grown increasingly dominant politically and economically, we’ve likewise grown increasingly out of touch with the values, perspectives and priorities of ordinary Americans.

When this elite constellation comprised a relatively small share of the population, they are forced to engage with, and consider, the broader public. For instance, in a world where less than 3 percent of Americans possess a college degree, as was the case in 1920, it would be impossible for degree holders to simply ignore everyone else. Professionals wouldn’t even be able to keep food on the table if they concerned themselves only with the highly-educated. It would be much harder for such a small voting bloc to control a major political party, orient entire cities around their whims, and dictate the flow of the broader economy in the U.S. and beyond. They would be largely unable to simply exert their will over others with minimal compromise or regard.

Today, more than 1 in 3 Americans 25+ has a college degree, and they’re increasingly consolidated alongside the wealthy into a small number of hubs, with tight networks of institutions that reinforce one-another (such as academia, the mainstream media, advocacy orgs, and left-aligned foundations). Under circumstances like these, degree-holders no longer have to engage much with the rest of the country. Knowledge economy enterprises can likewise easily sustain themselves by focusing only on superelites, other knowledge economy professionals, and the communities and institutions they inhabit in the U.S. and around the world. Academics, journalists, entertainment companies and other cultural producers can focus exclusively on the culture, values, and priorities of people like themselves and their superelite patrons with little concern (or even outright disdain) for being accessible, compelling, or useful to others. A political party can be flush with funds, and viable electorally, by aggressively pursuing the interests of professionals and the cities they congregate in at the expense of most others.

For example, voters with a BA or higher have comprised an outright majority of the electorate in Massachusetts, New York, Colorado and Maryland in recent cycles. Many other states hosting knowledge economy hubs are trending in the same direction. Studies have found that the effect of educational attainment on Democratic partisanship grows stronger as the share of degree holders in a county increases: as professionals grow less accountable or connected to ‘normies’ they align more homogeneously with the Democratic Party. U.S. cities associated with the knowledge economy are now more uniformly ‘liberal’ than they have ever been, and tend to be starkly segregated along political lines. According to estimates by Ryan Enos and his collaborators, roughly 38% of contemporary Democrats live in ‘political bubbles’ (where less than a quarter of one’s neighbors belong to the non-dominant political party) — largely as a result of how politically homogeneous most major cities have become:

“The most extreme political isolation is found among Democrats living in high-density urban areas, with the most isolated 10% of Democrats in the United States expected to have 93% or more of encounters in their residential environment with other Democrats… In major urban areas, Democrat exposure to Republicans is extremely low, especially in the dense urban cores. Notably, a large plurality of Democrat voters live in these areas and the very low levels of exposure extend even to the medium-density suburbs of these major areas and to minor urban areas.”

The rise of a new major donor class has exacerbated these divides. As David Callahan notes, the transition to the knowledge economy has led to the rise of a new constellation of millionaires and billionaires who retain most of the wealthy’s traditional aversion to regulation, taxes, trade protectionism and labor unions (and the aversion to focusing on issues like poverty and class per se), but who skew far ‘left’ on issues like environmentalism, gender, sexuality, race, immigration, criminal justice reform, and aggressively leveraging the state to address perceived social problems. These new millionaires and billionaires (and their families) comprise a growing share of the superelite.

Critically, these new knowledge economy oligarchs are not just to the left of the median voter, they are frequently to the left of Democratic activists on these issues (who, themselves, tend to be far to the left of the typical Democrat voter on ‘culture’ matters). And these superelites have poured immense sums of money into non-profit organizations, political campaigns, journalistic organizations and institutions of higher learning to move knowledge economy professionals and their preferred political party further in their preferred direction. Quite successfully. As economist Thomas Piketty and colleagues have demonstrated, the new ‘Brahmin Left’ has more-or-less fully ‘captured’ contemporary the Democratic Party and sets its agenda.

The effect of these consolidations has been huge. Comparative studies in the U.S. and other countries find that educated professionals have a bigger impact on sociocultural policy than rich people have on economic policy (and, as previously discussed, there is major overlap between the highly educated and the rich, reinforcing the hegemony of the free market + culturally liberal position, despite the dearth of Americans who actually subscribe to that position).

In response to the outsized influence of symbolic capitalists over the Democratic Party, those who feel unrepresented by knowledge economy professionals and our social order (including growing numbers of minority voters) have shifted towards the GOP. As Richard Florida demonstrated, ‘creative class’ workers have moved aggressively towards the Democrats in recent decades and are now by far the most staunchly Democratic labor group. Although ‘service class’ workers still lean left, they have been drifting consistently towards the Republicans since 2008. Meanwhile, ‘working class’ voters are now decisively Republican, and have been shifting still further ‘right’ over time.

This is, in part, because the reorientation of the party around knowledge economy professionals has not merely changed the substance of Democratic politics, but also the style. For instance, as compared to other voters, professionals tend to be much more impressed by charts, plans and data, and gravitate towards ‘policy wonks’ (who often hold limited appeal in a general election). Moreover, although they are alienating to most other voters, professionals regularly insist upon identitarian appeals to social justice and interpret those who decline to overtly focus on race, gender and sexuality as failing to be ‘real.’ Because our lives are oriented around the production and manipulation of symbols, we also place a lot of stock on things like representation, symbolic actions, performative demonstrations, ‘proper’ rhetoric, semantic distinctions, etc. — what Democratic strategist James Carville derisively described as ‘faculty lounge politics.’ In its bid to attract and mobilize professionals, the Democratic Party has increasingly adopted this kind of ‘academic’ messaging.

Indeed, even when the party wants to speak to non-elite audiences, these efforts are often hampered by the fact that the people developing the messaging tend to be highly-educated ideologues from relatively affluent backgrounds who often possess inaccurate ideas of what will resonate with their intended audience. And even when the message itself is solid, the people delivering the intended message — from sympathetic media figures, to social media advocates, to door-to-door canvassers — all tend to be highly-educated, relatively affluent, and ideologically extreme. And they tend to describe the party, its platform and its candidates in ways that reflect their own personal values and priorities, often speaking ‘off script’ in ways that alienate potential voters. That is, Democrats end up delivering ‘faculty lounge politics,’ even party leaders would rather not, because the party apparatus, from top to bottom, is increasingly dominated by knowledge economy professionals.

The Democratic Party is far from the only organization wrestling with the consequences of these shifts. Many traditionally class-oriented leftist organizations, from labor unions to the Democratic Socialists of America, have leaned increasingly heavily into ‘identarian’ conceptions of social justice and ‘woke’ symbolic politics as a result of being administered by knowledge economy professionals who have never worked ‘normie’ jobs. In turn, knowledge economy professionals have increasingly embraced these ostensibly class-based organizations. There has been dramatic growth in unionization and union action within higher ed, journalism, tech, gaming, television and movies – even finance! Membership in the Democratic Socialists of America has exploded, driven heavily by young professionals (although despite this growth its membership remains nearly 90% white and overwhelmingly male).

But as knowledge economy professionals have gravitated towards these organizations, many others have fled. Union membership in the U.S. is now at a record low. Unions are perceived as increasingly divorced from the rank-and-file workers, and more focused on pushing niche agendas of the college-educated folks that administer them rather than protecting jobs or improving pay and working conditions for members. There has been discontent and even lawsuits about the use of union dues to support controversial political organizations (like Planned Parenthood and Black Lives Matter) or Democratic Party candidates.

According to research by political scientist Oren Cass, the top reason non-union working class Americans mistrust unions is that they are perceived as being too political – and too focused on progressive cultural politics in particular (even as knowledge economy employers have tried to dissuade professionals from unionizing on the grounds that unions aren’t woke enough: enjoy ‘cancelling’ people whose behaviors and views you disagree with? Unions make that hard. Worse, any genuinely cross-class labor action would likely entail making concessions to ‘normies’ and their regressive views and backwards priorities. Who wants to do that?).

As I show in We Have Never Been Woke, efforts by corporations to recruit and retain knowledge economy professionals – both as customers and employees – have led them to become much more politically vocal, and to express views on politics that alienate most Americans but resonate strongly with the (most lucrative) constituencies they are most concerned about.

Across the board, it seems like catering to the niche preferences and priorities of knowledge economy professionals tends to come at the expense of the allegiance of most others – including and especially working-class voters across ethnic and religious lines. If the party has to choose between catering to professionals and virtually any other group, they should prioritize the latter every time.

At present, professionals are basically a captured constituency — the alternative, after all, is the party of Trump. This is a dealbreaker for us in a way that is not true for others. Non-white and less affluent or educated voters are not just willing to cross party lines due to their growing alienation with the Democratic Party, they’ve actually been doing it, in ever-growing numbers, over the course of the last decade – all the way through the 2022 midterms. The fact that labor is now a genuinely contested constituency between Biden and Trump says everything about the current political moment, and it’s nothing good.

Democrats don’t have a lot of margin for error in 2024. And the stakes of this election are genuinely enormous given Trump’s increasingly vengeful and unhinged state (even relative to his already-high 2016 baselines). This is not the time to indulge knowledge economy professionals and our idiosyncratic approaches to politics. Democrats should instead focus intensely on ‘normie’ middle class and working-class voters and let knowledge economy professionals fend for ourselves. We’ll make our way to the polling places just fine on November 5th no matter what, and overwhelmingly ‘vote blue no matter who’ all the way down the ballot. If Democrats want others to join professionals in voting ‘blue,’ they’ll have to meet these others where they are.

Originally published 12/4/2023 by The Liberal Patriot.

For still more on these themes, see this talk I did about two years ago which previews some themes for what became the second book. It hits some similar notes, but a lot of different ones. Including a tight focus on how gender plays into this story:

As We Have Never Been Woke elaborates, Great Awokenings are usually followed by right-wing gains at the ballot box. What happened in this electoral cycle is not an unusual outcome — it’s a case of something.

Many have been trying to sell Republicans for years on the virtues of being “socially liberal, fiscally conservative” including Pete Wilson, who crushed all opposition to his nomination for California governor in 1990 fairly easily. (He and a lot of the older Republican establishment dated from a time BEFORE the Republican Party became “pro-life.”) But lo, we found out that the main line of the public is the exact opposite of “socially liberal, fiscally conservative.” Bye!