Video Games Have Never Been Woke

The gaming industry has become far more symbolically liberal over the last decade. But it’s critical to contextualize these shifts.

After 2011 there was a major shift in how symbolic economy professionals thought about, talked about, and pursued “social justice.” As I demonstrate at length in my forthcoming book, these changes were visible along many different dimensions — cutting across the symbolic industries — and were largely exclusive to symbolic capitalists and the institutions we dominate (giving rise to a growing divide between “us” and everyone else).

One of the first places these changes (and tensions ‘about’ these shifts) became evident was the gaming industry.

This is, in part, because despite that fact that the professions associated with the gaming industry (such as graphic designers, creative directors, writers, software engineers and IT professionals) are overwhelmingly aligned with the Democratic Party, the gaming public is not.

In fact, by some measures at the time, gamers were evenly torn between the two major parties, and a plurality of gamers self-identified as “conservative.” The picture has not changed dramatically in more contemporary data: gamers are more likely to identify as Republican (and less likely to identify as Democrat) than American adults overall — and they remain roughly split between the major two parties (within the margin of error).

Nonetheless, after 2011, game critics and reviewers grew more focused on cultural and political issues, emphasizing progressive cultural themes. Sometimes they focused on elements like representation or the social message games more than the actual gameplay. Gaming forums followed suit. And gaming companies began responding to these social pressure campaigns.

For example, despite evidence at the time that games with female leads didn’t sell as well as games with exclusively male protagonists, companies began increasing gender representation. And in 2013, they had a breakthrough year for female protagonists with games like The Last of Us, Tomb Raider, and Beyond: Two Souls enjoying strong critical and commercial success.

The following year would be roiled by a culture war within the industry and its fandom, now known as #Gamergate. Purportedly annoyed by the growing overt left politicization of games and gaming culture, and expanding norms of ‘political correctness’ accompanying these shifts, a largely leaderless (and surprisingly diverse) movement emerged mocking, critiquing and defying the moralization of the gaming industry -- and doxing and harassing many of the people perceived to be leading the moralization campaign.

In vain.

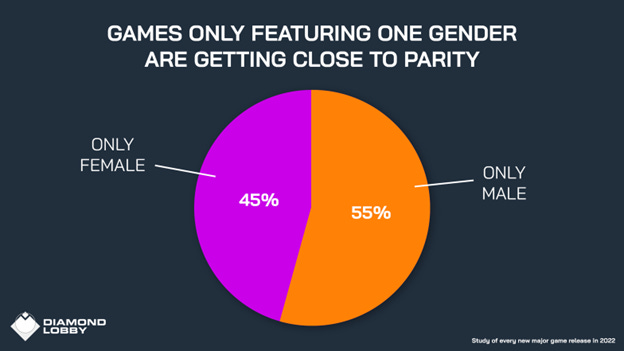

In 2012, industry analyst firm EEDAR (now acquired by NPD Group) analyzed games released on 7th generation video game consoles from 2005-2010. They found that only 4 percent of titles had exclusively female playable characters, although an additional 45 percent offered an option to play as either gender. 10 percent had protagonists of no discernable gender.

By 2015, a year after Gamergate began, and three years into the Great Awokening, the share of new releases with female-only protagonists had more than doubled: 9 percent of games announced at E3 (the premier industry trade show killed off by COVID) had female protagonists.

By 2020, that number had doubled.

In 2022, of games that featured playable characters of only one gender, nearly half featured women exclusively.

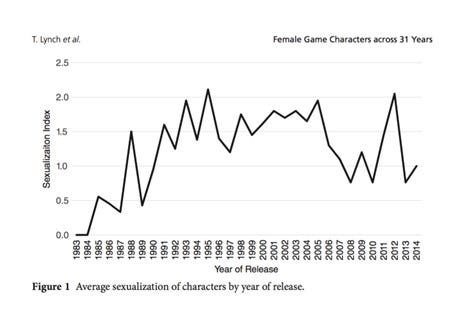

Female characters in games were also given more agency, and were less sexualized as compared to previous eras – with a sharp shift occurring after 2012.

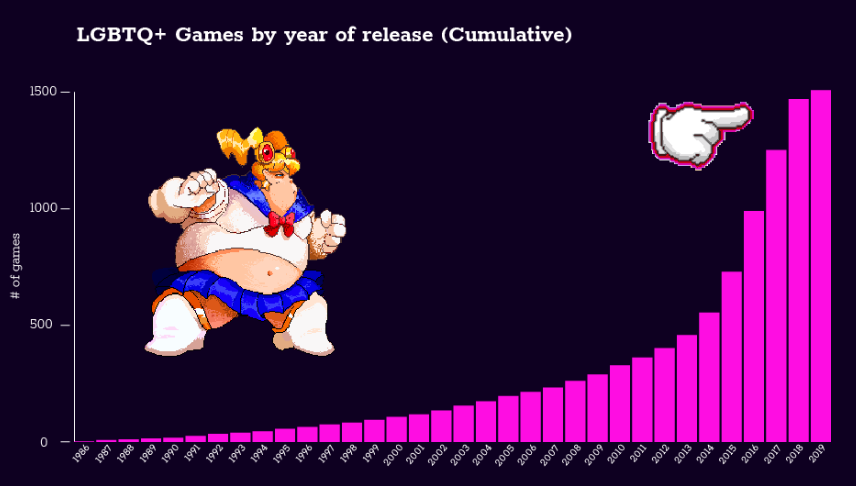

Critically, the representational shifts weren’t just restricted to gender. There was an exponential growth in LGBTQ representation in games over this same period. The year-over-year increase in total LGBTQ titles shifted from a steady modest gain each year into increasingly dramatic climbs from one year to the next — the rate of growth was itself accelerating rapidly — each year between 2012 and 2018. And then it returned to the usual stepwise increases thereafter (note that the graph was pulled unedited from the original report – not designed by me!):

And this growth was not just restricted to side characters. Instead, as the share of games featuring LGBTQ rapidly increased, the share of these games featuring LGBTQ characters as protagonists (as opposed to non-player characters, or NPCs) rose in tandem:

Ethnic diversity in games increased substantially too.

To set some baselines: a 2009 videogame census, the first of it’s kind, found that roughly 85 percent of video game protagonists in top titles published between 2005 - 6 were white. A subsequent study found that in 2010, even in role playing games that allowed players to design their avatar, most did not allow for the creation of non-white characters. Much has changed in the intervening years.

Between 2017 and 2021, less than 10 percent of games had exclusively white protagonists. More than 1 in 20 games had no white protagonists at all (much like the forthcoming Assassins Creed Shadows, which takes place in 16th Century Japan and features two playable characters: a Japanese woman and a Black man).

Overall, the share of contemporary video game characters who are white is roughly identical to the percentage of Americans who identified as “white alone” in the 2020 U.S. Census (61.2%).

And it almost goes without saying, but, virtually all contemporary games that allow players to design their avatars now incorporate a broad array of skin tones. Most also incorporate myriad options for hair textures, facial features, body styles, and so on — allowing people to produce characters representing whatever ethnicities they’d like (although some continue to do this better than others).

Finally, alongside the shifts in representation along the lines of race, gender and sexuality, there was a huge emphasis on “accessible gaming” over the period in question.

As part of this push, developers increasingly offered in-game content warnings (despite the fact that these warnings typically don’t work as intended and may actually be counterproductive) -- and provided many more options for players to censor or avoid things that might “trigger” trauma responses or phobias.

Meanwhile, games continued to follow the pre-Awokening trend of being unrelentingly hostile towards organized religion, to the extent that religious themes are meaningfully explored at all.

Hence, if #Gamergate is correctly understood as a culture war provoked by increasing diversification and liberalization of video game content and video game culture, it is a conflict that the “reactionaries” would seem to have lost unequivocally.

But, of course, this does not necessarily entail that “social justice” prevailed…

Metagame

In terms of revenues, the global video game market completely swamps most other entertainment sectors. And the industry is set to eclipse its only true competitor, paid television, any day now.

Indeed, adjacent industries, such as streaming services, are developing interactive programming and acquiring game libraries. Musicians are doing concerts in Fortnite. As superhero fatigue seems to be setting in, adaptations of video games are increasingly seen as future cash cows movies and television shows. News media organizations like the New York Times increasingly rely on games like “Wordle” to generate revenue that subsidizes their reporting. Esports competitions are coming to the Olympic Games in 2025. Politicians have done live events and run political ads in video games — or try to make themselves relatable to younger voters by picking up a controller.

Games, however, are not just an increasingly dominant form of pop culture – many other (non-entertainment) sectors of society are being transformed in their image.

Gamification -- the application of game systems such as competition, quantifying player/ user behavior and doling out rewards (tokens, badges, levels, and so on) based on performance or progression – is increasingly being integrated into everything from education, to the workplace, to online platforms and even political struggles or “social justice” advocacy.

And so, at first glance, the apparent stakes in the struggles over “wokeness” in video games would seem to be immense. It seems hugely consequential that the gaming industry is dominated by Democrats and has grown far more progressive in its symbolism over the last decade.

Appearances, however, are often deceiving.

Games and Thrones

Although games often try to be “relevant” by gesturing towards contemporary struggles and current events, studios tend to aggressively deny their work has a political agenda.

These claims are often met with eyerolls because it’s not a secret that game designers are overwhelmingly aligned with the Democratic Party, and this clearly shows in how they choose and depict the “hot topics” they evoke. Just like in most other spheres of cultural production.

But the kernel of truth is, even when games are blatantly political in their themes, the translation of those themes into the world in which we live is often a murky and confused process. It’s a process powerfully undermined by other shifts that have simultaneously occurred over the last decade.

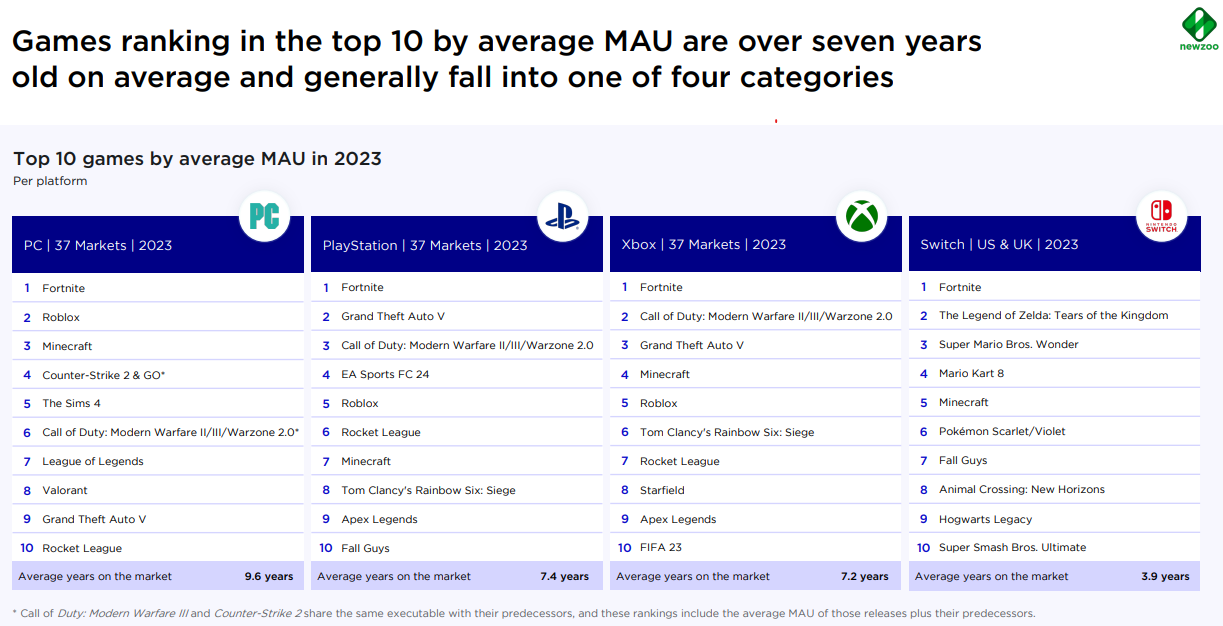

For instance, in addition to growing more diverse, games are also getting longer and longer. As a consequence, much like most other arenas of pop culture, a small number of titles are capturing ever larger sections of players time, money, and attention – and staying in their dominant position for much longer periods of time. In 2023, for instance, across platforms, the games with the highest numbers of monthly annual users were more than seven years old on average. 60 percent of all videogame playtime in 2023 was spent on titles released at least six years prior.

In tandem with these shifts, games have been growing dumber: there has been a marked decline in titles that emphasize strategic thinking and planning. In their place, has been a rise of “utopian work simulators” – games that keep players busy and engaged for untold hours by never-ending chains of checklists, tasks and side-projects; ever-expanding skill trees, upgrades and loot tiers (enhanced by microtransactions); expanding suites of systems, stats and cosmetic options for people to optimize on; new trophies for people to reach. These “compulsion loops” grant a sense of productivity, accomplishment and forward momentum that many seem to be missing in their “real” lives.

In fact, growing numbers of young men are dropping out of the actual labor force so they can dedicate more time to the “utopian work” of gaming.

That is, rather than doing anything about the aspects of their lives they find unappealing (let alone organizing with others to address bigger issues) – instead of working to improve the world we live in -- people are increasingly choosing to escape into alternative worlds where things are simpler, more rational, and fair. Worlds that literally revolve around them — designed to cater to their preferences — where even other characters’ sexuality fundamentally turns on the whims of the player (instead of endowing NPCs with specific – and therefore exclusionary – preferences).

These alternative worlds are so seductive and satisfying that growing numbers of Americans are literally substituting video games for sex. Men who are heavy gamers seem to have reduced sex drive. It seems they’re getting their dopamine hits from racking up points instead of trying to score with the ladies (gay). Meanwhile, there is evidence that, among women, forming fictional relationships with between their avatars and non-player characters can dampen their desire to seek out romance IRL (in real life). Dating the guy down the street, after all, could never compare to getting ravished by Haslin (bear sex, am I right?).

These developments are a feature, not a bug, of how these products are designed. Gaming companies regularly collaborate with psychologists, cognitive and behavioral scientists and neuroscientists to make their games as addictive as possible — to hijack our brains in the service of maximizing playtime and engagement while extracting as much money out of players as they can.

To the extent that these efforts are successful — in a world where growing numbers of players can barely be bothered to keep the lights on or try to get laid — people definitely aren’t going to be dedicating meaningful effort to advancing inconvenient forms of social change. To the extent that gaming content is “political,” therefore, it ends up producing a sterile form of politics: politics from the armchair — more expressive than substantial.

Put another way, the more successful a game is at capturing and holding users’ attention, the less consequential its social messaging becomes, as users grow less likely to act on whatever beliefs they may hold insofar as active participation would come at the expense of their playtime (and require less pleasurable kinds of effort for less immediate psychological rewards).

More to the point, it’s important to keep in mind at all times that the main reason companies try to make their games “relevant” — the reason they evoke contemporary events and political themes — is to try to increase sales. Their primary goal is to move units (and, perhaps secondarily, enjoy critical acclaim). These same considerations drive their emphasis on diversity.

Beyond Representation

To the extent that commentators focus on progressive cultural symbolism in games, it is often to the expense of attending to their substantive content — the things characters actually do while under the players’ control.

Is it “woke” that we can now play as a woman who kills anyone standing in the way of our objectives – stealing, looting or otherwise appropriating anything of value that we come across in the process – while destroying tons of infrastructure in the pursuit of our objectives? (it’s what ‘heroes’ do!)

Is it “progress” that you can now play as a trans person mowing down criminals and enemies of the state extra judiciously or, alternatively, play as a queer mercenary or robber?

Is it a major moral victory that disabled people can now virtually enact the violent colonization of alien planets on behalf of private corporations just like the rest of us?

Does it undermine the status quo that we now have Black avatars in utopian work simulators too?

The answers to these questions don’t seem obvious to me.

More importantly, to the extent that people focus intensely on gaming companies and their outputs as culture war actors, they can lose sight of the reality that the main thing they are: business enterprises.

In fact, profit motives clearly undergird many of the observed shifts in representation.

For instance, the shifts in gender are tied to the reality that nearly half (45%) of U.S. gamers are women. Although men and boys are more likely to play for long periods of time and to identify as gamers – datapoints like these ultimately suggest far more room for growth among women (whereas men are likely approaching their upper bounds of consumption).1

With respect to sexuality, queer Americans are more likely to play games, and spend significantly more money and time on games per capita, as compared to cisgender heterosexual counterparts. This makes them a lucrative demographic for studios to target.

Gamers are increasingly ethnically diverse as well – and there is a lot of room for growth beyond “traditional” (white and Asian) gamer demographics.

In terms of class, highly-educated Americans are one of the fastest growing consumer markets for video games – and one of the most lucrative business markets overall. Consequently, it is a sound business bet to ensure games reflect the norms and values of the people who tend to graduate from college (even at the expense of alienating “others”). And, of course, trying to appeal to this market is tantamount to game developers inserting their own values into their games, because jobs in this sector near-unanimously require a college degree. The demographics and preferences of game developers are not far removed from symbolic capitalists as a whole (with both diverging sharply from “normies”).

One problem companies face, however, is that professionals producing video games are not particularly diverse (more on this soon). Consequently, the desire to include a more diverse range of characters in a way that will actually resonate with the target populations (and, thereby, increase sales and engagement) has created a need for game studios to rely on outside consultants to help flesh out their characters, themes and plotlines while avoiding red flags. In practice, these consultants serve a function akin to “sensitivity readers” in publishing: they generate highly constrained and minimally “problematic” forms of identarian representation that help companies signal the “correct” affiliations, avoid lawsuits and PR nightmares (involving constituents they actually care about).

Those who characterize these moves as “woke” impositions often seem to miss the point. For instance, by obsessing over the public profiles and social interactions of the often eccentric folks who do this work in the American market, they fail to see the fundamental continuity between how companies navigate the “culture wars” in the United States and the ways they censoriously tailor content with an eye towards international markets -- preemptively neutralizing elements that would aggravate political authorities and other key stakeholders. In both cases, the behaviors and tactics are similar. In both cases, the goals are the same: maximizing market access and market share. The emphasis across the board is decisively on “doing well” over “doing good.”

These moves may ultimately prove to be misguided from a business perspective in particular cases.2 However, this should not lead people to forget that fiscal considerations are ultimately what govern these decisions.

Keeping in mind that gaming studios are fundamentally businesses trying to edge one-another out in hypercompetitive global markets – foregrounding how their content is developed, published and distributed primarily in the service of that goal – this can help us move beyond the “woke” veneer that many companies exude, allowing us to better attend to their actual organizational incentives and practices.

Loot System

Although the gaming industry outputs may convey an impression that companies strongly prize diversity, equity and inclusion, in practice the industry is highly parochial and hierarchical.

Most positions are consolidated in a small number of symbolic hubs. Degree requirements exclude more than 60 percent of Americans right out of the gate – and an even higher share of non-whites and people of lower class backgrounds.

Indeed, although there has been a major shift in ethnic diversity within games over the last decade – to the point where the share of white characters in games is roughly equivalent to the share of white people in the broader population – the racial and ethnic trends of game developers has been basically a series of flat lines over this same period:

Shifts in the gender composition of developers have been more robust. However, more than three quarters of this workforce continues to be male. And women who are included in the industry tend to be concentrated in lower-paying, lower-status, and less executive roles.

Gaming companies, game streaming platforms, and gaming culture, are also notorious for sexism, sexual harassment and sexual abuse. There is a ‘frat boy’ culture that runs throughout the industry, wherein male employees feel comfortable engaging in brazen harassment of their female peers — even as male executives attempt to prey upon female staff, and often retaliate if their overtures are rebuffed.

With respect to sexual orientation, compared to most U.S. workers, game developers are especially likely to identify as queer. By some estimates, more than one in four game developers identify as something other than cisgender heterosexual. All said, there may be more LGBTQ people (who comprise less than 8 percent of the broader U.S. adult population) designing games than there are females of any orientation (who are a majority of American adults). Yet, despite their heavy footprint in the industry, queer, trans and non-binary developers also report widespread mistreatment and experience lower pay relative to straight peers.

Yet, as pronounced as these contradictions are, there’s a sense in which dwelling on specific identity-based challenges faced by different industry constituents threatens to ‘lose the ball’ — because gaming companies are notoriously terrible to workers across the board, demographics be damned.

For instance, the gaming industry is known for its intense ‘crunch culture’ with workers made to put in extreme hours (often 80+ per week in the lead-up to a release), many of these unpaid, while subjected to intense pressure and abuse; they are regularly threatened with being stripped from the credits and blacklisted if they burn out or resist. Worse, rather than celebrating and rewarding successful product launches, these periods of ‘crunch’ are often followed by widespread layoffs, as studios seek to cut costs and juice share prices between major projects.

This is how gaming companies treat their actual employees. However, a huge part of the video game labor force is comprised of (perma) ‘temps’ who work in the office alongside ‘employees’ but receive much lower pay, no benefits, worse treatment, are typically not mentioned in the credits, have absolutely no job security — and who are expected to perform at an even higher level of productivity, and without complaint, if they want any hope of ever being converted into a full ‘employee.’

Beyond exploiting domestic laborers, the game industry is increasingly maximizing profits by outsourcing the most repetitive and labor-intensive parts of production to the Global South — where companies can demand even higher levels of productivity, on tight time constraints, without being encumbered by Western-style labor protections and wage standards at all. And studios increasingly threaten to outsource or automate3 still more positions if employees get too uppity or unionize.

As organizer Alex Speidel put it, “It’s a passion industry. People get into [the games industry] because they love [gaming], and workers are willing to accept exploitation and low wages because we make the games we love.” Employers have largely rendered an acceptance of this state of affairs as a condition of working in the industry at all — social justice discourse notwithstanding.

Not a Game

Up to now, we have just been discussing the development of software. But, of course, gaming consoles are physical objects, and video games continue to be printed heavily on physical media.4 Here, the industry’s impacts and practices are also abysmal.

For instance, the extraction and refinement of key materials for gaming devices are intimately bound up with violent conflict and slave labor. The assembly of consoles often likewise involves human rights violating forms of labor exploitation.

Both the production of physical games and gaming systems, and the data centers and servers that fuel software development, have devastating environmental impacts — consuming massive amounts of water and energy while producing tons of waste.

Meanwhile, unsold inventory and outdated equipment (in the wake of new console generation launches) end up getting dumped in Global South countries, where they pose significant challenges for the environment and people’s health.

I could go on, but I suspect the picture is, by now, quite clear: since the outset of the Great Awokening, video games have increasingly evoked progressive cultural themes. However, to focus on these symbolic gestures – to take the cultural signaling at face value – is to miss more fundamental truths about these organizations and their outputs.

In reality, the gaming industry has never been woke. To focus intensely on corporate messaging is to miss the actual impacts these companies and their products have on society, which are often far out of step with their progressive rhetoric. To obsess over culture war posturing in industry outputs is to neglect the arena of competition that these companies care about most — the primary objective that supersedes and subverts everything else they do — the struggle to dominate their rivals and maximize their profits.

8/28/2024 update

Over at

, journalist put together a 10 year retrospective on GamerGate, featuring perspectives from lots of interesting folks. I'm one of those folks. My observations follow below. You can check out everyone else's takes here.Q: What is the long-term legacy of Gamergate? How did it influence mainstream culture and politics over the past decade?

Gamergate was significant because it was one of the early indicators of a period of rapid cultural and normative change and contestation that began after 2011 and began to wind down a decade later. #Gamergate is often understood as blowback against game developers and the gaming community growing more concerned about "social justice" issues in the early 2010s. But as I illustrate at length in my forthcoming book, game developers and reviewers were not unique in becoming more concerned about representation, inequality and social injustice at that time. There were simultaneous movements in the same direction that were observable in academic research, journalistic articles, entertainment outputs and beyond.

Across the board, people who work in the "symbolic professions" became more politically active and engaged -- and focused more intensely on issues like racialized and gendered inequalities, LGBTQ rights, environmentalism, and supporting people with atypical bodies and minds. #Gamergate was one of the first indicators that something was changing. It was also a preview of the culture wars to come:

People who work in the symbolic professions generally have political views and modes of engagement that are different from "normies." These differences grew larger after 2011, because people like "us" changed while most other Americans were pretty stable. And the differences also grew more salient, because people who work in symbolic fields grew more assertive in pushing their moral vision on others, and grew more confrontational and intolerant with respect to perceived injustice, bigotry or bias. This created an opportunity for right-aligned folks and anti-woke culture warriors to enhance their own position by vowing to bring these institutions and professionals "under control" or return them to their "proper" purpose. #Gamegate was a preview of how an "Awokening" can devolve into a culture war of this nature.

Nonetheless, over the decade that followed, video games and video game discourse became much more concerned with social justice issues and representation. The brutal realities of the gaming industry changed very little but the outputs changed a lot. So, regardless of whether we take #Gamergate participants at their word about what they were trying to accomplish (i.e. reforming the industry), or if we instead defer to the prevailing narratives about what #Gamergate was about -- either way, the movement was an unambiguous failure. But it was a prescient failure, previewing the tumult that would unfold throughout the symbolic professions in the decade to come.

Among men and boys, as discussed in earlier sections, games are already crowding out their productivity and diminishing their social reproduction. Studios can’t squeeze much more engagement or revenue out of them than they’re already providing. Continued growth, therefore, requires expanding beyond the “traditional” consumer base of white and Asian men. And because the traditional constituency is largely “captured” (they aren’t, realistically, going to stop gaming in the foreseeable future), studios have a lot of leeway to experiment with broadening their consumer base, even at the risk of annoying their existing customers. And so, it seems as though they’re doing just that.

Sometimes games’ attempts at cultural relevance and inclusion fail to resonate with consumers as intended. They can come off as clunky and distracting in a way that generates mockery, or detracts from players’ enjoyment of the game, even among those not particularly invested in the culture wars (in no small part because, as I detail at length in my forthcoming book, many of those who purport to speak on behalf of or otherwise ‘represent’ various constituencies are not very representative in truth). There have been some high profile “woke” titles in recent years that have been held up as exemplifying this risk. But some inferential caution may also be appropriate in these cases:

In most contemporary cultural industries (books, shows, movies, etc.), new releases barely earn their money back, if they’re profitable at all. Hit titles, by definition, have always been outliers rather than serving as the rule. And, as discussed above, it’s actually gotten harder for new I.P. to break through and enjoy success, as older titles have been dominating an ever-growing share of sales and user playtime.

Without keeping these realities in mind, it can be easy to overinterpret or misinterpret a game’s lack of success. There is a high chance for a release to be a financial ‘failure’ regardless of it’s symbolism or messaging. Often, when a “woke” game flops, it’s overt politics may not have helped, but they were clearly not the title’s primary issue. This is one reason why studios have not simply ended their reliance on cultural advisors: they don’t think the cultural symbolism was actually “the problem” in the games that failed. And they might be right!

Game developers are intensely worried about the impacts of AI on their jobs. It should be noted, however, that exploited humans in the Global South undergird a lot of work misleadingly described as being powered by “A.I.” In practice, ‘automation’ in this field is largely outsourcing by another name — or, more precisely, outsourcing paired with '“ghost labor.”

One might think that downloading and streaming games might be more environmentally friendly than continuing to produce physical media. However, this is not necessarily the case. As one recent analysis puts it, “Over the past decade, digital game downloads have risen in popularity. For most games, digital downloads use less energy, but for the largest games, energy use by the internet data centers providing the download can rival the energy needed to produce and transport physical discs.” Streaming games from the cloud in high definition if often even less efficient.

This has to be the worst researched article I have read from you.

1) You call those who disagree with you reactionaries, which shows your obvious political bent.

2) You are not a gamer. If you were, you would be aware that there is a huge disconnect between the legacy gaming press, which you constantly reference and gamers. The gaming press, tends to be far left. Gamers are not. In you want to hear the other side listen to YouTubers such as Critical Drinker, Nerdrotic, Geeks and Gamers, etc. You do not have agree with those views, but you have to be aware of them. In the word of John Stuart Mill, He who knows only side on side of the case know little of that" Quite frankly I am disappointed that you chose to hear only one side. You are better than that

3) There are people who play games and there are gamers. You are correct that both men and women pay games, but gamers are overwhelmingly males in their teens, 20's and 30's. When game studios overlook this, they lose money. Take for example Suicide Squad, Kill the Justice League. That one game, widely derided as woke, lost Warner Brothers $200 million, Star Wars Outlaws, in which the prime character looks like a 40+ year old woman, will likely suffer a similar fate.

4) You are correct, making money should be the prime objective of any company. But before you can make money, you have to get money. Larry Fink, CEO of Blackstone, which manages nearly 10 trillion dollars in assets, is the father of ESG, He stated in 2017, "You have to force change. You do that by requiring companies to have ESG programs in place to get VC or PE funding. So, Game studios have to keep their PE/VC partners happy, as well as their fans. That is extraordinarily difficult. The result has been that many smaller gaming studios have gone out of business and some of the larger ones are hurting. Meanwhile Asian studios, unencumbered by ESG, are booming.

There has been a widely held assumption in the entertainment and other industries that you will add new costumers if you go woke and still keep your old ones. That has proven not be true. The old ones leave in droves. Lucas Studios, the prime example of this, has yet to make back their purchase price of the studio from George Lucas. You can make a lot of money selling high fat ice cream to your demographic and be far left (Ben and Jerry's) It doesn't work nearly as well when you are selling Bud Light, tractor supplies or woke games.

5) Instead of calling the other side reactionary, you should actually listen to them. You do this in your other areas of research. Who knows? You might actually learn something.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful and thorough information on video games :-) a gamer at heart, I appreciate the attention to detail here. A long time ago I decided to not play online games anymore, download my games once only, do not use physical support anymore, and enjoy my only consol ever bought in the US (a 10-year-old bought-used PS4). We don't have to stop playing, just accepting the reality if our world (physically limited).