You Ask, I Answer: We Have Never Been Woke FAQ

My responses to reader and audience questions about the book and its themes

Since the publication of We Have Never Been Woke, I’ve been blessed to travel around the country (and soon, internationally) and talk to different stakeholders about the book and its themes.

Through in-person events, social media engagement, and this Substack, I’ve gained a window into how folks are processing the arguments of the text. I’ve done tons of interviews with journalists and podcasters of all sorts of backgrounds to think through the implications and applications of the work. And the book has been reviewed widely, from prestige outlets, to political sites, to ideas focused publications, and beyond. I’ve been honored to discover that both the critical and commercial response has been overwhelmingly positive.

It's been raucous and contentious at times. It’s been alternatively exhausting and exhilarating. It’s been gratifying to see this thing that was a file on my computer now existing as an actual object in the world – an object that lots of people are engaging with, learning from, and making use of in their own domains.

Put simply: it's been a real privilege to think with all of you over the last five months about how the rise of the rise of the symbolic professions has transformed U.S. politics, economics and culture – and to wrestle over the historical, current and ideal future role of symbolic capitalists in society. Across all these discussions and domains, there were a handful of objections, and ideas that have consistently surfaced. This post will highlight questions and concerns that I think are most interesting and/or important to respond to. In the process, I’ll get to double-click on a few points that, in retrospect, I wish I’d have delved into a little more within the text itself.

It’s a problem that a book called We Have Never Been Woke doesn’t define “wokeness.”

But is it though?

As I explain in the introduction, the title of my book is a nod to a different text by another sociologist: Bruno Latour’s We Have Never Been Modern. His book argued that the stories we “moderns” tell ourselves about what separates us from other people actually obscure the nature of the modern world and inhibit our ability to properly understand and address the problems of modernity. In a similar vein, We Have Never Been Woke argues that the stories symbolic capitalists tell ourselves about how we’re champions for the vulnerable, marginalized and disadvantaged in society tend to obscure how social problems come about and persist, who benefits from them and how -- thereby undermining our ability to realize our professed social justice aspirations.

Leaning into this association, journalist and sociologist Gary Younge argued in The Idea’s Letter that “A significant part of the [We Have Never Been Woke’s] problem can be found in [al-Gharbi’s] title. Latour at least defines modernity before claiming it never existed.” This is a strange claim… because it’s not true at all. The closest Latour comes to a concise definition of modernity appears roughly a tenth of the way into the body of the text when he tells us that “the word ‘modern’ designates two sets of entirely different practices which must remain distinct if they are to be effective, but have recently become confused.” Over the paragraph that follows, he identifies these two practices as translation and purification. The end of that paragraph is followed up by this diagram:

Is everyone clear on what “modernity” is now? Likely not. So Latour proceeds to elaborate, eventually sketching out a “constitution” of modernity – comprised of four core guarantees (that derive from two central paradoxes). It’s then, roughly a third of the way through the book, that readers gain a robust understanding of how Latour views modernity and its discontents (postmoderns, antimoderns, et al.), and they come to understand what is meant by the claim “we have never been modern.” However, there is nothing even remotely approaching a straightforward, dictionary-style, tweet-length definition of “modern” or “modernity” anywhere in the book. What’s more: it isn’t necessary for Latour to provide such a definition in order for readers to understand his argument.

It’s worth belaboring this point because, after mischaracterizing Latour’s book, Professor Younge spends about half of the critical portion of his review chastising me for not defining “woke.” He wasn’t the first. For instance, my interview with On Point (NPR) got testy for a bit because the host was eager for a straightforward definition that could settle the debates around “wokeness” once and for all, and this was something I was not remotely interested in, much to her frustration.

In my view, people overfocus on definitions in a way that often distracts from substance. In some circles, it’s claimed that if you can’t or won’t define a term, then you must not know what it means. Absent definitions, they suggest, one is unable to use words ‘correctly’ (such that your meaning is consistently well-understood by your audience). But as I explain in the text (pp. 29-31), this is balderdash. It’s not the way language works at all, not even for banal expressions and words. But “woke” isn’t just any word. It’s a highly contested term. As I write in the book, if I had simply paved over these disputes to advance a clean definition that suits my own moral, political, or scholarly project -- this would be far less clarifying than what I decided to do instead, which was to surface how different stakeholders have understood and mobilized “woke” across time.

I spend several pages, right at the outset of the first chapter, going into the history and contemporary usage of “woke” including explorations of the different ways people have tried to define the term, and the different postures various stakeholders adopt with respect to it. And it’s not just “woke” that gets this intensive treatment. The book identifies and analyzes the evolution of other words that have served a similar discursive function in the past (such as “political correctness”) to help contextualize the current and likely future trajectory of “woke.”

Thereafter, I provide a list of beliefs and dispositions that people across the political spectrum seem to associate with “wokeness” (pp. 31-32). I explore the prevalence of these dispositions in American society, showing that they are most common among institutions and constituents associated with the symbolic professions (and they’re really uncommon among people who are not relatively-affluent, highly-educated, urban and suburban whites). I conclude the first chapter by providing a historical account of why these beliefs came to be associated so robustly with the symbolic professions and got bound up with our claims for wealth, status and autonomy (pp. 57-66).

All of this provides a much richer understanding of how people understand the term than a simple dictionary definition would. But, strikingly, none of this rich detail about what “wokeness” means was mentioned in Professor Younge’s review, or in the remarks of others who criticize the lack of a dictionary-style definition. Based on their characterization, you’d think I just thumbed my nose at clarity, and then moved on to other topics, deploying the term throughout the text in a capricious way – inviting, or in any event, allowing others to follow suit.

Younge argues that, “since [al-Gharbi] does not own the word [‘woke’] he cannot control how it is understood and employed beyond the covers of his book.” This is unquestionably true. But of course, even if I had defined the word, I would not be able to “control how it was understood or employed beyond the covers of my book.”

Kimberle Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, et al. “owned” critical race theory. This did nothing to stop Christopher Rufo from unapologetically branding everything he didn’t like “CRT.” Nor did it stop Republicans from effectively capitalizing on the moral panic Rufo successfully engendered around the term. Likewise, Marxists “own” communism. This doesn’t stop many on the right from branding everything they don’t like as some form of “communist” (including branding wokeness as “postmodern neo-Marxism” or “cultural Marxism”).

Definitions are not magic spells that bind the political opposition. As I explore at length in the book, even if you introduce a new term into the “language game,” you can’t control how it is interpreted and used once people start engaging with it en masse. If you’re talking about a century-old term that’s already highly-contested, forget about it. There is simply no way that providing a definition of “woke” in my book would have somehow ended the culture wars around the term. Those insisting that it’s necessary to provide a definition seem to misunderstand how both language actually works, and how politics actually works.

Again, I do spend significant time in the first chapter helping readers understand the history and contemporary usage of the word “woke.” But then I move on… because the book is not actually about wokeness.

It’s a problem that a book called We Have Never Been Woke does not seem to care about “wokeness” per se. For instance, it does not genealogize, taxonomize, or evaluate the correctness of “woke” ideas.

If you pick up a book called A Jaguar is Not a Jaguar: Why Automakers Lean on Animalistic Imagery, you probably won’t learn much about the diets and habitats of large jungle cats, their closest evolutionary cousins, and so on. This is because it’s not a book about jungle cats. It’s transparently a book about the auto industry and the ways they market their products. In a similar vein, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite is not a book *about* wokeness. It’s a book about the rise of a new elite formation and the ways they mobilize social justice discourse in their struggles over status, resources and opportunities.

A Jaguar is Not a Jaguar: Why Automakers Lean on Animalistic Imagery should not just illuminate the specific marketing decisions of the Jaguar company, it should also shed light on why Dodge makes “Rams” and “Vipers,” Chevy makes “Impalas,” Ford makes “Mustangs” and “Broncos,” and Volkswagen makes “Beetles.” It might even help readers understand why companies in other industries (such as the footwear company “Puma”) make the branding decisions they do — insofar as they have similar types of objectives and considerations for their products. In a similar way, We Have Never Been Woke: The Cultural Contradictions of a New Elite is not narrowly focused on progressive symbolic capitalists. It applies a symmetrical lens to conservatives and antiwokes within this coalition (much to their consternation at times), detailing how they are driven by the same mix of motives; they share similar ways of thinking, talking about, and participating in morality and politics; they rely on similar legitimation strategies around meritocracy and the common good. The titular “cultural contradictions” run throughout this new elite formation – they aren’t unique to the “woke” (any more than animalistic imagery is unique to the titular Jaguar company in the hypothetical book above).

In the same way that it would be a strange tangent for A Jaguar is Not a Jaguar to spill a lot of ink exploring the mating behaviors of large jungle cats, or the ways they use feces and urine to mark their territory, it would have likewise been a major digression for We Have Never Been Woke to try to genealogize or taxonomize various beliefs associated with “wokeness,” or evaluate their moral and epistemological correctness.

Put simply: if you want a book about wokeness, you’ve come to the wrong place. The good news for these readers is that the publishing market is absolutely saturated with “wokeness studies” books -- some good, some less so. For contrast, my own book explores the political economy of the symbolic professions from the interwar period through the present. Everything from the marketing material, to the introductory content, to the body of the text stresses this point: it’s a book about elites, not beliefs.

With respect to said elites, the book is not particularly interested in the contents of their hearts and minds. In fact, a core argument of the book is that internal states matter far less for understanding society than behaviors, relationships, or allocations of resources and opportunities. To the extent that the book engages with research in the social psychological, cognitive and behavioral sciences, it is purely to help readers understand how symbolic capitalists can simultaneously

Be sincerely committed to “social justice” (however defined)

Actively benefit from, exploit, and perpetuate the very social problems they decry, and leverage “social justice” discourse in the service of their ideal and material interests, AND simultaneously

Remain convinced that they are the “good guys,” and that the problem are “those people” who think, feel and say the “wrong” things about race, gender, sexuality, and so on (even if they benefit less from the prevailing order, and exert less influence over the systems and institutions, than “we” do).

That is, I only talk about “hearts and minds” at all to explain how people can mobilize “social justice” in self-serving ways without being cynical or insincere. I take sincerity for granted both because I think it’s actually the case that most people are sincere and because, at bottom, I’m not really interested in anyone’s sincerity (or lack thereof).

In the same way that A Jaguar is Not a Jaguar: Why Automakers Lean on Animalistic Imagery would be ill-served by spending one or more chapters examining the bases for zoologists to distinguish leopards from jaguars, it would be orthogonal to my research project spend lots of time parsing who “truly” believes in social justice (and on what basis). I take sincerity for granted precisely so that I can sidestep discussions like these. For the purposes of this book, I am totally uninterested in “beliefs” or “ideas” per se. I’m interested in the social life of moral and political claims about social justice – how they are mobilized in the public sphere, by whom, and in the service of which apparent ends. And I’m focused almost exclusively on things that can be readily observed from the outside: what people say, how they behave, and so on.

Given that We Have Never Been Woke is not actually *about* wokeness, why use this highly-polarizing word in the title?

Some of my colleagues who’ve published New York Times bestselling books told me to change the title. They advised me to go with something less mysterious and more declarative. Princeton University Press urged me to reconsider the book’s title too. They were concerned because the term “woke” has today become something of a slur. As the book itself highlights (p. 29), “woke” is a word that virtually no one uses in a positive and unironic sense anymore. Hence, they argued, including the word “woke” in the title may send signals that I (or more precisely, they, at Princeton) don’t want to send.

No matter where you fall on the moral or political spectrum, “woke” is a highly-contentious term. Based on the title, many on the left have indeed assumed that the book must be a culture war screed, a myopic and reactionary text, and/ or a sensationalist cash-grab. Meanwhile, based on the title, many on the right have assumed the book’s argument to be that either:

The whole discussion about “wokeness” is just an empty moral panic. There was never really a “there” there. Or,

The problem is that institutions and society haven’t gone all-in hard enough on the idiosyncratic forms of politics and morality discursively associated with “wokeness.”

On all counts (on the left and right), my argument is basically the opposite of these folks’ apprehensions. But to discover this, prospective readers have to get past the title.

This raises a legitimate question of why I was so insistent on placing “woke” front and center… despite the fact that, again, the book is not actually about “wokeness.” In earlier versions of the book, I answered this question in-text. In the final version, this content ultimately got struck for efficiency — so let me answer it here.

We Have Never Been Woke is a tome with a century-spanning historical arc that was clearly written for posterity. I wrote it with the aspiration that it might still be read many years from now, possibly with multiple editions.

However, it’s also the case that books are products of particular times, places and circumstances. Precisely because of the long time horizon of the book, it felt important to me to “ground” the text in the historical and cultural milieu from whence it emerged. No word has been more central to the contemporary period of tumult within and around the symbolic professions than “woke.” For this reason, the term served as a useful anchor for the book and its themes. The fact that “woke” is such a contested and evocative word is something I view as a virtue rather than a problem. The same holds for the ambivalence and ambiguity many read into the title.

Certainly, I understand the desire for a more clear and less controversial title — from a marketing and PR standpoint on the one hand, or for assuaging people’s moral and political apprehensions on the other — but this was a book designed to unsettle. I wanted to bake that into everything, title included. And I was relieved that Princeton University Press trusted my vision for the work enough to let it ride.

It’s hard to know if I would have moved more units by adopting an alternative title and framing for the book. But it’s clear that, as things stand, the book has been a critical and commercial success to a degree that few university press books ever reach, and relatively few trade titles for that matter (for more on the typical reach of academic press and popularly-oriented books, see pp. 191-192 of We Have Never Been Woke). So even if my preferred title may not have maximized readership, it doesn’t seem to have radically undermined it either.

Why focus so intensely on symbolic capitalists for understanding contemporary society? What about the politicians, military leaders, and so on? Aren’t they the ones with the real power?

The “we” in We Have Never Been Woke is a constellation of elites that I call symbolic capitalists – professionals who work in fields like finance, consulting, law, HR, education, media, science and technology. Starting in the interwar period, and accelerating after the 1960s, there were changes to the global order that radically enhanced the position of these elites and their professions in society — transforming the contours of social inequalities, their bases for legitimation, and much more.

According to some, my focus on this novel elite constellation is misplaced. It’s other people who truly call the shots in society. The rest of us are, apparently, just helpless pawns in their game. For instance, in his review for The Ideas Letter Gary Younge rhetorically asks, in the review he rhetorically asks, “When the concentration of wealth and power is escalating at the rate that it is, wages have been effectively stagnant for the best part of half a century, economic and racial inequalities are growing… where is the evidence that academics, consultants, lawyers and journalists dominate much beyond their own realms?”

To put it mildly, the evidence is overwhelming.

To frame this point, let me begin with a reminder that the U.S. has three branches of government, each with distinct powers and responsibilities:

Let’s briefly walk through each, starting with the judiciary:

Symbolic capitalists have an entire branch of government dedicated entirely to us. From top to bottom, the judicial branch is comprised exclusively of symbolic capitalists. And this branch plays a really important role in shaping inequality and other social phenomena. As Katharina Pistor powerfully illustrated, capital is literally a product of legal coding. The rich and powerful, alongside monopoly-oriented corporations, protect and reproduce their social position through regulatory capture and other legalistic means. If you want to understand the concentration of wealth and power, it’s hard to see how you get there while ignoring the role of the law and lawyers.

With respect to the legislative branch, according to contemporary New York Times estimates, more than 70 percent of House representatives are former white collar professionals. Rates in the Senate are even higher than the House, and among Democrats the frequency is higher than Republicans. Chapter 4 of the book also shows that Congresspeople are much more likely to respond to concerns of symbolic capiltalists, and conform to our preferences, as compared to most other constitutencies in America. Not only are most legislators symbolic capitalists, but symbolic capitalists are their core constituents. On many levels, symbolic capitalists dominate the legislature in addition to completely controlling the judiciary.

What about the executive branch? Here’s a fun fact: every Democratic president since Jimmy Carter has been just one variety of symbolic capitalist: a lawyer (failed Democratic nominees Kamala Harris, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, Mike Dukakis and Walter Mondale were lawyers too. Al Gore, meanwhile, was a different type of symbolic capitalist: a journalist). For the past 40 years, there hasn’t been a single Democratic nominee (successful or failed) who wasn’t a symbolic capitalist.

On the Republican side, symbolic capitalists have been hugely influential too: Richard Nixon was a lawyer. Ronald Reagan was an actor. The last GOP candidate before Donald Trump (Mitt Romney) worked in consulting and finance. Trump’s likely successor, JD Vance, is a veritable symbolic capitalist sampler platter: a bestselling memoirist, a finance bro, and an Ivy League credentialed lawyer by training.

Here you might be thinking: but what about the Orange Man? He’s not a symbolic capitalist! He made his money through his construction companies, right? This is what Trump wants people to believe, but it simply isn’t true.

Donald Trump’s real estate and construction businesses generated consistent losses. As a Forbes analysis showed, if he just took the money he inherited and invested it in the S&P 500 instead, he’d have accumulated far more wealth than he did through his real-economy businesses, which bankrupted him multiple times. In fact, as an excellent New York Times report illustrates at length, the actual sources of Donald Trump’s present-day wealth and status were regular appearances in television, movies and commercials and then licensing his “brand.” Donald Trump is a symbolic capitalist through and through. Had he not pivoted to the symbolic industries, he’d probably be broke right now (and he’d quite possibly have faced jail long ago for financial improprieties, having never had a chance to run for office).

But I should here stress that the relationship between Trump and the symbolic professions is highly symbiotic. Trump didn’t just make a lot of money from the media and entertainment industries, these same industries have and continue to make a lot of money off him too. Trump’s ability to generate attention and engagement is a major factor in the wall-to-wall coverage of everything he’s said and done for the last 10 years straight. If it’s a story about Trump, symbolic capitalists (the primary consumers of contemporary media content) eat it up. Whether with love or hate, we can’t get enough.

All said, every single U.S. president has been a symbolic capitalist for 20 years straight now (and for more than a decade, each president’s opposite-party rivals have been symbolic capitalists too. It’s been symbolic capitalists v. symbolic capitalists for each of the last three cycles).

As it relates to the people with the guns: the U.S. has a civilian-controlled military, and the POTUS is also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. Given that symbolic capitalists have controlled the presidency for more than 20 years straight, we can see that if want to understand the projection of U.S. military power in modern history, we have to look at the symbolic professions for that as well. In fact, the role of symbolic capitalists in directing and legitimizing U.S. foreign policy has been immense for most of the last 50 years, as Noam Chomsky previously illustrated with respect to the Vietnam War, and James Mann showed for the War on Terror. But setting aside the role symbolic capitalists have played in managing and manufacturing consent for these conflicts, even if we just look at who is directly calling the shots, it’s been symbolic capitalists serving as commander-in-chief for an unbroken two decades. There are children who were born, and who are now almost old enough to drink, and there hasn’t been a single non-symbolic capitalist who served in the White House during their lifetime. That’s wild.

In truth, symbolic capitalists absolutely dominate each single branch of the government, and we have for some time. Hence, if Younge wants to understand “the composition of the Supreme Court and the evisceration of reproductive rights, voting rights and gun control that has come with it” his analysis should clearly start with the symbolic professions. Symbolic capitalists aren’t a distraction, we’re the main event.

And so far, I’ve just talked about the public faces of power. Yet, as C. Wright Mills observed in The Power Elite (a landmark text exploring the interrelationships between corporate, political and military leaders), “The power elite are not solitary rulers. Advisors and consultants, spokesmen and opinion-makers are often the captains of their higher thought and decisions.” As true as this was in 1956, it is far more relevant today. A huge and growing share of political decision-making and policy implementation is now carried out by unelected, nontransparent, and largely unaccountable advisory bodies and bureaucrats. Expert testimony, analysis, recommendations and projections play a huge and growing role in policymaking, court cases, and other domains.

I dedicate multiple chapters of the book to driving home how symbolic capitalists define contemporary society and politics. Chapter 3 details at length how wealth and power have been consolidated into institutions, professions, and communities associated with the symbolic economy over the last century, at the expense of many stakeholders in society. I detail how colleges and universities increasingly serve a gatekeeping function for deciding whose perspectives and priorities are worth taking seriously, or who is viewed as suitable for consideration for upper middle class jobs and lifestyles — and given the uneven distribution of education across society, the growing reliance on these credentials has reinforced social inequalities and undermined social mobility.

Chapter 3 also illustrates in great detail how the stagnation that Younge alludes to seems to be a product of the transition to the symbolic economy. Meanwhile, the racialized inequalities he condemns are actually far more pronounced in institutions and communities associated with the symbolic professions than elsewhere. In fact, symbolic capitalists benefit from these inequalities more than most: our lifestyles and social position are fundamentally premised on exploitation and exclusion. If Professor Younge was not persuaded by the extremely wide array of empirical literature I marshal on these points, it’s hard to see how he could possibly be persuaded by any amount of evidence given that, in his own words, I “examine almost every aspect of [symbolic capitalists’] lives from who they sleep with, vote for, donate to, what they read, earn, eat and spend and where they live and study, to make the case.”

What about the actual capitalists?

One of the most common replies to the arguments of We Have Never Been Woke has been, “What about the millionaires and the billionaires?” This type of refrain has dominated symbolic capitalist discourse since Occupy Wall Street.

As a matter of fact, the dreaded “1 percent” do hold a large and growing percentage of resources in the U.S. and beyond. As I detail in Chapter 3, the top 1 Percent closed out 2022 controlling 26 percent of all America’s wealth. Let’s be clear: this is a radically disproportionate share. More than a quarter of America’s wealth is in the hands of just one percent of its population.

Notice, however, that the “1 Percent” do not control a majority of U.S. wealth. They don’t control anything near a majority. Consequently, if you just focus on the top 1 Percent, you actually miss the overwhelming majority of U.S. wealth.

What if we zoom out to the upper quintile — if we look at the billionaires alongside the upper middle class? Well, in that case, we can account for 71 percent of the country’s wealth. Another way of saying this is that the bottom 80 percent of Americans make do with roughly one-quarter of the country’s wealth, because super-elites and the upper middle class gobble up the rest.

Another thing you immediately notice when you zoom out to the upper quintile is that percentiles 2 through 20 collectively control much more wealth than the top 1 percent – over 50 percent more. But this wealth is conveniently rendered invisible when we focus tightly on the pinnacle of the wealth distribution. As Richard Reeves put it, narratives like “we are the 99 percent” primarily serve to help people will more than a million dollars in assets and healthy six-figure incomes pretend to be “ordinary Joes.” It’s super convenient for affluent folks to portray themselves as “middle class,” and to define themselves in contradistinction to the billionaires, who purportedly deserve all the blame for social problems. Yet, as Reeves’s research illustrates, opportunity hoarding by folks in the upper quintile drives rising inequality and declining social mobility much more than the actions of the top 1 percent.

It does nothing for, say, Waffle House workers to deny this reality, and to pretend like someone with a million dollars in assets and a household income in excess of $175,000 is in the same financial “boat” as themselves. “We are the 99 percent” is a discourse that primarily serves the interests of the wealthy, not the poor (indeed, as Chapter 2 of my book illustrates, Occupy Wall Street was a symbolic capitalist movement through and through).

A core project of We Have Never Been Woke is to zoom out beyond the top 1 percent, to see a fuller picture of wealth and power: who owns it, how it is acquired and maintained, how it is leveraged, and towards what ends. Ironically, it is precisely for this that Professor Younge and others accused me of having “erected a system of thought about how society works that bears little relation to the system of power.” Yet, in truth, it’s impossible to understand how power actually operates in society today without looking at symbolic capitalists.

A quick example. Anand Giridharadas’ Winners Take All explores how billionaires and the corporations foment all manner of social problems through the myopic pursuit of profit maximization, and then they leverage high-profile philanthropic investments to paint themselves as the solution to those very problems. There’s a way of analyzing this phenomenon focused strictly on the billionaires and capitalist enterprises per se. This would be the “radical” option. But it would also miss most of the actual story.

If we try to think in concrete terms about how and why things happen, it quickly becomes clear that the billionaires don’t actually do much of anything in the mystification process Giridharadas describes. The billionaires are not designing and implementing their own PR strategies, interviewing themselves for the news, and then writing, publishing and disseminating their own puff pieces. They aren’t drafting and implementing their own contracts or administering their own nonprofits.

Who are the PR professionals that help spin these donations into positive perceptions while minimizing negative publicity for the harm they cause? Who are the journalists who write the fawning profiles after these donations, helping them launder their reputations? Who are the folks who administer these nonprofits through which the super-rich attempt to influence society? Who moves the money and documents around to make all this possible? The answer in each of these cases is “us,” the symbolic capitalists. We’re the ones who actually do the things. Every single step in the process happens with us and through us and literally could not happen without us. Or in the words of symbolic capitalist Taylor Swift:

Put simply, if you want to understand the system of power, you can’t focus narrowly on the super rich. This point is stressed at length throughout We Have Never Been Woke, but some book reviewers have had a really hard time internalizing it. One retorted, “Symbolic capitalists can ‘shape’ and ‘constrain’ only to the extent they further the goals of those with the power to set system- or institution-wide goals—i.e., real capitalists.”

Not only is this flatly false, the book is full of concrete examples illustrating how and why it’s flatly false. For instance, Chapter 3 walks readers through transformations at the Ford Foundation (pp. 133-134). The foundation was created by auto magnate Henry Ford to support medical care and basic science in the Detroit area and beyond. During the second Great Awokening, administrators decided to transform it into an institution that funded queer, black liberationist, feminist, environmentalist, and socialist research and activism in the U.S. and abroad. Henry Ford II was outraged at this turn, and demanded the organization return to its original mandate. He tried multiple paths over a long period of time to make this happen, and was flouted at every turn — a struggle that culminated with his resignation. An American oligarch went to war with symbolic capitalists about the direction of his own family foundation, and he lost.

This is not an isolated case.

In the current (fourth) Great Awokening, symbolic capitalists ran roughshod over their bosses for more than a decade. We sowed institutional chaos and unrest that often spilled out into the public causing massive PR problems. We pushed companies to regularly deliver cultural products that “bombed” and advertising campaigns that backfired because we insisted on ham-fistedly injecting our preferred moral and political messaging into everything we did – with devastating impacts for many companies’ bottom lines. We shoved many of those “with the power to set system-wide and institution-wide goals” off of their perches (including, memorably, ousting traditional capitalist “Papa John” from the pizza company that bears his name -- for speech crimes!). And that’s just looking at the economic sphere!

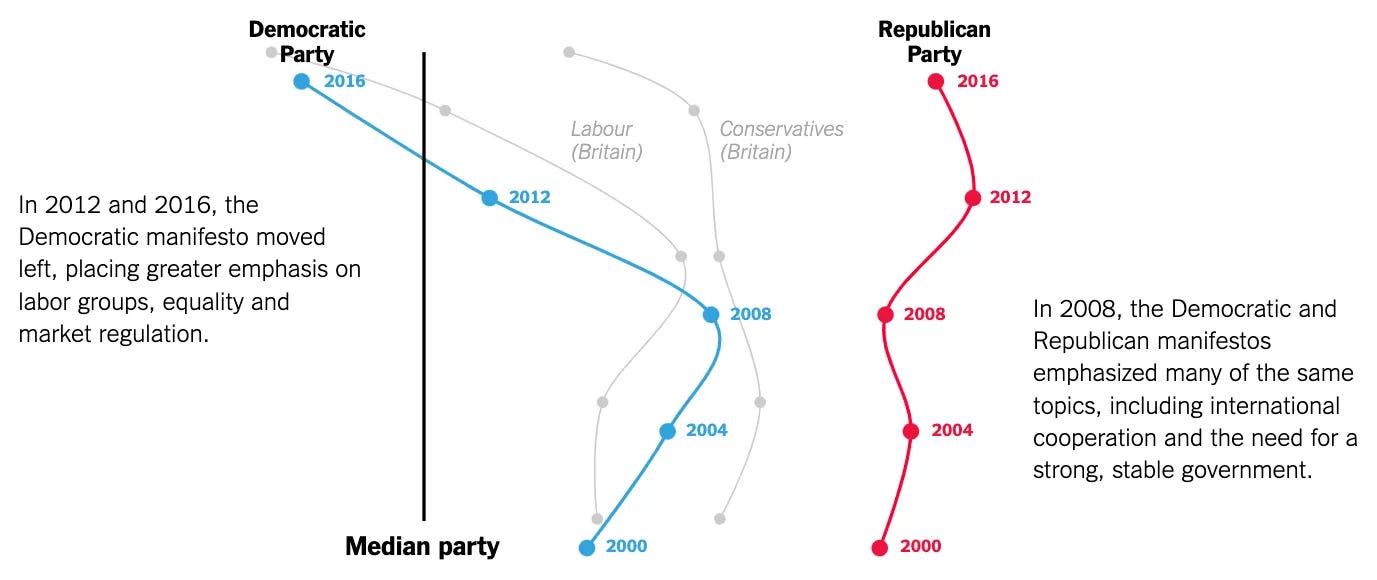

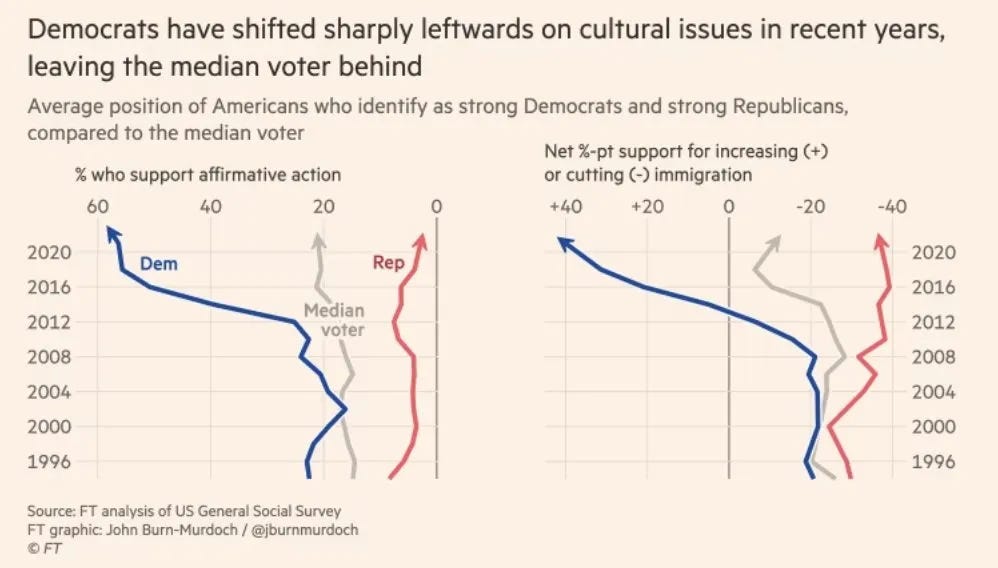

In terms of politics, symbolic capitalists completely bent an entire political party to their whim, pulling the Democrats hard “left” on cultural issues after 2010 (while insisting the party continue advancing our idiosyncratic economic interests at the expense of normie voters), devastating the party’s ability to succeed in national races. What we’ve seen over the last fifteen years hasn’t been politicos instrumentally conforming with symbolic capitalists’ preferences only insofar as it was useful to them – we’ve seen politicians engaging in electorally-suicidal behaviors in a desperate (and futile) attempt to appease people like us.

Politicians and employers only started to reassert their authority in the last few years, after symbolic capitalists began moderating of their own accord. The Great Awokening didn’t end because corporate leaders and politicos asserted their power to squash it. Quite the opposite: these leaders were only able to assert their power because the Awokening was already winding down. Put simply: when symbolic capitalists choose to exercise it, we have lots of power — even against the top 1 percent, the executives, the politicians, et al.

The problem is, we don’t often use our backbones. This is in part because the type of people who get folded into the symbolic professions tend to be more risk averse and conformist, and less solidaristic, than most other people. But it’s also because we profit immensely from the work we do, right alongside the billionaires and multinational corporations we serve. We comply because we want to: we’re eager to get ahead, to ingratiate ourselves with people in power, etc. And we aren’t super honest about these realities — not to others, not even to ourselves.

Instead, as Chapter 6 explores, symbolic capitalists tend to espouse a highly-selective form of helplessness. We have no problem coordinating and flexing our power when it comes to things that we find personally gratifying and instrumentally useful. When it comes to blacking out Instagram squares, insisting that people explicitly acknowledge their privilege, casting ballots for Democratic candidates, etc. we don’t say things like, “individual sacrifices and behaviors don’t matter.” We say individual action is both important and necessary. We solve all sorts of coordination problems to coerce our preferred behaviors out of others including, again, our institutions, bosses, political representatives, and so on. But when it comes time to put actual “skin in the game” — when addressing a problem would require us to incur real risks or sacrifices, to change our own aspirations, lifestyles, and so on (or when it’s us who face scrutiny for causing or benefiting from social problems) -- then all of a sudden we hear “drop in the bucket” and “coordination problem” arguments. In these cases, we tend to gravitate towards narratives that the only real “solution” for the problems under consideration would be to completely burn down and reinvent the system… anything less is worse than useless… and because “the revolution” isn’t happening anytime soon (certainly not a leftist revolution), it seems there’s nothing left to do except resign ourselves to enjoying our elite lives, albeit with occasional pangs of guilt and bouts of self-flagellation. As arguments go, these rhetorical moves are super embarrassing. But they’re also incredibly common, including (and especially) in discussions about my book.

But what’s most striking to me about this type of objection is that, even if this I simply conceded this rhetorical move — we agreed to ignore the pesky specifics of how things actually happen and just focus narrowly on the super rich — this would do little to actually turn the gaze away from the symbolic professions. Even among the “1 percent,” the traditional capitalists are not where the action is these days.

Consider the Forbes Real Time Billionaire’s List – a regularly updated calculation of the richest people Earth. At time of writing, if you attend to the 10 wealthiest people on the planet, you’ll notice a few things. First, they’re all men. The patriarchy may be down, but it isn’t out. Second, 8 out of the 10 richest people on earth are Americans (USA! USA! USA!). Finally, the richest Americans are nearly exclusively symbolic capitalists. The companies through which they attained their wealth include Facebook, Oracle, Google, Berkshire Hathaway, Microsoft and Amazon.

With respect to Amazon, I’ve occasionally been presented with an objection that Jeff Bezos is not a symbolic capitalist. After all, he’s the guy who packages to your doorstep every other day, right? Those aren’t symbolic goods, they’re real! While it’s definitely true that the sweater you ordered online (when you could have simply bought one from a brick and mortar store) is not a symbolic good, those who think Amazon primarily traffics in physical goods don’t really understand the company’s business model at all.

Amazon does not actually make money by sending packages to your door – the company takes a loss on most of those transactions. Goods are regularly sold below MSRP (with devastating impacts on many local businesses and the communities they serve). The company generally spends more on shipping than they collect in shipping fees or Prime subscription revenues (to say nothing on the immense expenses they incur from “reverse logistics” to conduct returns and exchanges). In fact, the online marketplace is such an economic drag that it took Amazon roughly seven years to earn a profit for the first time. They had to work out a revenue model that relied on something other than mailing underpriced goods to consumers in the U.S. and abroad.

Most of the positive cashflow generated by Amazon.com doesn’t come from product sales, but from advertising. The website is primarily a conduit for delivering ads to consumers and collecting ad revenue from sellers. The merchandise delivered to your doors is just a means of harvesting your data and serving you ads on behalf of their real clients – the advertisers. Similar realities hold for all other aspects of Amazon’s business:

Prime Video: Amazon typically spends more on acquiring content than they take in from subscription revenues and digital rentals or purchases. The main point of the digital content is to collect consumer data, deliver ads, and expand consumption of content on behalf of Amazon’s clients. The Alexa-powered Echo devices follow the same logic. They were intended as tools to harvest user data and deliver ads. The devices themselves were typically sold at cost or at a loss. But, to date, the company has been unable to successfully monetize the Echo, so they shut down most of that division and discontinued its products. They’re now trying to launch a new line of Echo devices that use AI-tools to better harvest user data and nudge people towards buying particular products or consuming specific content on behalf of advertisers. It remains to be seen if this latest venture will also flop. But, critically, none of these initiatives are Amazon’s main source of revenue. That honor goes to their Amazon Web Service data collection, analytics and storage enterprise. AWS is their primary breadwinner and it’s not even close.

Across the board, Amazon is primarily in the data business and, secondarily, the advertising business. All the other products and services they offer are just ways to collect more data and deliver more ads. Put another way, Jeff Bezos is fundamentally in the same business as Mark Zuckerberg. Amazon and Facebook generate income in the same ways. Accordingly, the only U.S.-based “traditional” capitalist in the top 10 richest people in America is Elon Musk.

Musk’s companies and wealth do derive primarily from physical goods and services such as shipping and logistics (Space X), material extraction (The Boring Company) and auto manufacturing (Tesla). However, even Musk amassed his first hundreds of millions from two symbolic economy ventures: Zip2 (software) and PayPal (finance). And currently, Musk is trying to make big plays into other symbolic industries like UX (Neuralink), telecommunications (Starlink), social media (X), and AI (Grok). Hence, even the exception helps prove the rule: if you want to understand contemporary oligarchs, the symbolic professions are where the action is.

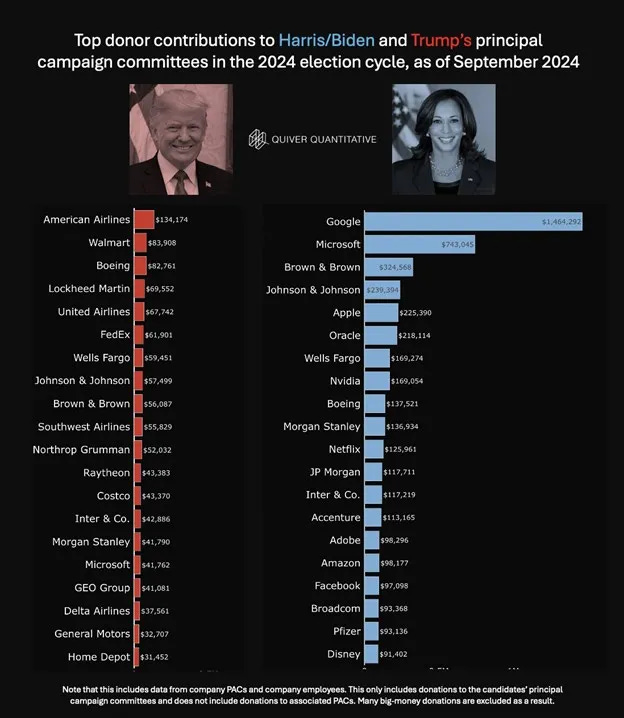

Likewise, if one wanted to understand, say, the influence of money on politics today, symbolic capitalists are the big story. As I detailed at length in a previous essay, there was a clear divide in which industries and companies supported which candidate in the 2024 election: the symbolic professions were aligned with Democrats, while companies oriented around providing physical goods and services backed the Republicans.

Critically, the amount of disclosed donations and dark money from symbolic capitalists towards Democrats far exceeded the amount of money raised by Trump and the Republicans on behalf of traditional capital. That may have been part of Kamala’s problem.

Chapter 4 of We Have Never Been Woke details how these new symbolic economy oligarchs tend to fall far left of the median Democrat activist on “culture” issues (and the activists tend to be significantly to the left of rank-and-file Democrats who are, themselves, to the left of the median voter). Money from these culturally-left donors and foundations has played a major role in subsidizing left-aligned cultural outputs and dragging the Democratic Party and aligned activist organizations further and further out of synch with the U.S. mainstream. If you want to understand growing alienation from the Democratic Party, you’d be better served by looking at symbolic capitalists — both the super elites and the rank-and-file — than by focusing on right-aligned industries and influence campaigns.

That said, for those interested, my next book (in active development) will turn the analytic lens the “other” way, exploring the constellation of elites, industries, communities and constituents associated with “traditional” capitalism (who have been increasingly consolidating into the Republican Party). If you want to understand “those people” better – stay tuned. But I viewed it as more urgent to write about symbolic capitalists first — in no small part because companies associated with the symbolic professions actually own and control most of the “real” economy too. For instance, decisions about whether a plant remains open or if workers continue to receive their pensions are increasingly made by folks who work for McKinsey or Goldman Sachs in addition to (or more typically, instead of) turning on the whims of traditional capitalists.

What’s striking is that folks seemed to have no problem understanding these realities when former Bain Capital executive Mitt Romney was running for president on the Republican ticket. But now that consulting and finance firms have become symbolic champions of causes like Black Lives Matter, feminism and LGBTQ rights (often coercing other companies into adopting the same posture) and donate primarily to Democratic politicians, the thread has somehow been lost. We’ve apparently reached a point where a prominent left-aligned scholar and journalist like Gary Younge could credulously ask whether consultants et al. actually influence society – likely provoking many readers to nod along with his rhetorical question. This is a distressing psychological transformation since the onset of the latest “Great Awokening,” but it only underscores the urgent need for my book.

You’ve sold me on your basic argument. What should I do now? How can I be part of the solution instead of exacerbating the problems?

A typical formula for books is to spend six chapters describing a problem and then spend the final pages speculating about solutions. These solutions-oriented sections are often the weakest parts of the book. There is often insufficient space to really unpack the suggestions with much depth or sophistication. The proposals tend to be overly simple in light of the complexity of the previously-discussed problems and, typically, they aren’t properly scaled to properly address the problem. I didn’t want to offer a tacked-on and half-baked section like that.

More to the point, I wanted to deny readers any sense of catharsis or any illusion that there are easy answers. I wanted readers to sit with the weight of these problems and to, themselves, really think about the implications and application for their own lives, communities and institutions (whose specific circumstances and operations I may not be as familiar with).

My publisher didn’t love this. I had to push to end the book on a willfully unsatisfying note. I ultimately won them over by stressing that it would be a non-sequitur to spending 300 pages on a hundred-year survey of the political economy of the symbolic professions… and then conclude with a list of steps for effective social justice advocacy. It is to Princeton University Press’ credit that they acknowledged this point and allowed me to end the book in the manner I found most appropriate. It was a choice they went into well-aware that many readers would walk away from the book frustrated by the lack of resolution.

Again, the text’s ambivalence, and readers’ frustration at said ambivalence, were “features” rather than “bugs.” But they did lead to some testy exchanges during the book tour.

At one stop, I concluded my talk and opened up for Q&A, and a group of older white ladies made a bee-line towards the microphone. Each of them asked versions of the same question. It took each of them two minutes or more to get to the punchline because they all included a lengthy preamble about how deeply and passionately committed they are to social justice, all the good things they’ve done in their lives, and how they’re “comfortable but not really rich,” and so on. All as a windup to asking versions of, “So we’re good, right? I’m good?”

I declined to provide this absolution to them because, for one thing, on what basis could I possibly provide it? But after consistently frustrating their desires for validation, and complicating the self-narratives in their preambles, one of them literally screamed at me, “well, what would you have me do?!” My response to her and to anyone with a similar set of sentiments is:

I wouldn’t have you do anything. I’m a social scientist who wrote a book on the political economy of the symbolic professions from the interwar through the present. No more, no less. If you want someone to give you guidance or provide absolution, consult a priest or a therapist. Or consider a self-help book instead of a sociology text.

If the book raises uncomfortable questions for you about how you’re living your life or the role you’re playing in the social order – that’s great. But the only person who can actually answer those personal questions is you. I can’t solve your emotional distress, help you adjust your life and relationships, or restructure the ways you allocate your time, energy and resources. These are things that each of us has to take responsibility for with respect to ourselves and the institutions and communities we belong to.

And, of course, even if I tried to provide individualistic advice (against my better instincts as a sociologist), people would have a hard time “hearing” what I’d have to say because, as Upton Sinclair put it, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

For instance, at one recent talk I drew from pages 146-148 of the book to emphasize how many professional families make dual-earner strategies work by offloading “women’s work” to other women (other women watch kids, prepare meals, clean the house, care for the sick, elderly, pets, and so on). I stressed how two-professional households often pay these women subpar wages so they can profit from their own family’s second salary despite purchasing tons of domestic labor from these other women. I highlighted how they often target undocumented women for this labor because they can pay them far less than U.S. citizens, demand more out of them, and treat them worse (because these migrants don’t have the same legal recourse with respect to wages, working conditions, etc. — if they make a problem, they risk deportation, and their clients know this and exploit it). Critically, I stressed, for those families who rely on undocumented immigrants to fulfill domestic roles, there’s no law that says they must be paid less than a U.S. citizen would accept for the same work. That is a choice families make. They see someone who is desperate and vulnerable, they know they can get away with shafting them on wages, and so they do that, enabling them to maximize profits from their second salary despite purchasing tons of “women’s work” from others. And, critically, they often think of themselves as “feminists” while engaging in these behaviors, in virtue of the fact said exploitation allows wives (in heterosexual couples) to aggressively pursuing careers alongside their husbands.

After the talk, a woman cornered me and pleased with me for advice on behalf of her “friend.” She said her “friend” is one of those people who hires undocumented caregivers and pays them less than she would a citizen – but she only because their family can’t afford to pay a more livable wage. They’re already living at the ends of their means, she said.

I replied that, “living at the end of one’s means” is a product of lifestyle choices. A family can more easily thrive within their means by making different decisions about where they live, whether or not they need to wear premium clothes, consume premium foods, or send their kids to private schools. They can adjust the extracurricular activities they fund, the travel they take, the cars they drive, and so on. Indeed, if a family is truly living at the edge of their means, they should consider making these kinds of changes independent of the pay they offer to caregivers and other domestic help.

Ultimately, I stressed, economic decisions are not about money. They’re reflections of what people value and prioritize. If people are so committed to advancing their own careers, living in particular neighborhoods, engaging in particular modes of self-presentation, building their personal wealth, and trying to ensure that their children reproduce their own elite position – to the point where they consume a lot of domestic labor to enable their lifestyle but don’t have a lot of money left over to pay said workers a decent wage – they can’t also say they’re deeply committed to paying their workers more but they can’t. It’s a choice to prioritize one’s elite lifestyle and their family’s elite reproduction over taking care of the people who make your lifestyle possible. It’s a choice that people can make differently by adjusting their lifestyles and reallocating their resources.

When I said this to her, she replied, “so I guess, what you’re saying is, I should tell my ‘friend’ to be more aware of her privileges and advantages.” Shocked, I replied, “No. My advice is that your ‘friend’ should pay her workers more, and adjust other aspects of her lifestyle to make that possible if she’s going to keep relying on domestic labor… although another option also available to your ‘friend’ and her family is to make more radical reconsiderations of how she and her husband divide domestic responsibilities — and more fundamentally rethink their aspirations and lifestyle choices — so they can rely on less purchased domestic labor to begin with.”

She didn’t seem to love that answer. It’s almost certain that her “friend” won’t take my advice. What this woman seemed to be hoping for was a way that she could solve this labor issue through deeper awareness of social injustice, or by better purifying her heart and mind. She wasn’t looking for practical advice so much as spiritual guidance.

There is a real appetite for someone like me to serve as a secular imam for anxious liberals. But I didn’t abandon my aspirations towards serving the Catholic Church only to become a priest on behalf of HR departments, nonprofit organizations, and progressive cultural advocacy groups. Indeed, it’s tough for me to imagine a more pathetic life trajectory than that.

As I observed in one of my favorite interviews about the book and its themes (about 36:36 minutes in), and as I note in the book (pp. 266-267), I view Ta-Nehisi Coates as a cautionary tale here. He did work that he thought was critical and challenging but, in his own self-description, found himself transformed into the guy “white people read to show they know something.” In his own estimation, his work became worse as a result: he couldn’t get meaningfully edited or challenged within his organization. Anything he produced, people just lapped it up and said, “give me more,” almost regardless of what was on the page. He was greeted with reverence wherever he went. He found this intolerable, and so he took a hard step back from the non-fiction world and resigned from his post at The Atlantic. He only reemerged recently to take a position on an issue that he knew would genuinely divide his former readership and alienate his former employer. While I respect that choice, I don’t want to be the next Ta-Nehisi Coates… in no small part because Coates himself grew tired of being Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Alternatively, consider Ibram X. Kendi. He wrote a decent (if troubled) book that garnered him a lot of fame, and then immediately and willfully succumbed to the temptation of becoming a secular priest. Coasting on the success of his book on the history of racism, he began producing “how to” guides for antiracism, first for adults, then kids, then babies – each text finding a way to be somehow worse than the last. As white guilt reached a crescendo following the murder of George Floyd, Kendi raised tens of millions of dollars from billionaires, multinational corporations, and aligned nonprofits for an antiracism center that produced very little work and was famous for its hostile climate. He recently resigned in disgrace from his position at Boston University — albeit with one hell of a golden parachute, having already accrued several million dollars from speaking fees, royalties, licensing deals, and so on, and with an offer in-hand to start a new institute (and raise tens of millions more dollars from anxious white liberals) at Howard University. It seems as though the faculty at Howard are less than thrilled with this arrangement, but the university seems more concerned about the money Kendi could bring in than with concerns about whether Kendi is actually a good scholar, whether existing faculty want him there, and so on.

If I wanted to become an “anti-Kendi” or “alt-Coates,” the pathway is clear to me, and it’s lined with gold. But it’s a road I’m not remotely interested in travelling.

To be clear: the “what should we do?” question is important. In many respects, it’s the question. But I suspect that the answer to that question is not going to come in the form of simple and universalistic statements. It’ll be context dependent and complicated. And, frankly, there are many scholars better suited to think through concrete solutions than I am (such as people who work in public policy and adjacent fields).

An aspiration of We Have Never Been Woke was to spur further research, discussion, and policymaking on the themes and problems explored in its pages. But the specific direction things go from here is something we’ll have to figure out together. It’s not for me to decree. I’m in no position to do that, and I don’t want to be either.

Doesn’t the book’s presentation of human nature run contrary to the idea that symbolic capitalists could or would improve?

Chapters 4 through 6 of We Have Never Been Woke demonstrate that:

People tend to perceive, think about, and describe the world in ways that advance their interests and further their goals

These self-serving biases are significantly more pronounced among the type of people who get folded into the symbolic professions, and

Social justice discourse can exacerbate these biases. In contexts where individuals, their peers, and the institutions and communities they belong to regularly depict themselves as allies of the marginalized and disadvantaged in society, people can become more likely to engage in inequality-reproducing behaviors while growing less able to recognize how they (and the people and institutions they identify with) contribute to social problems.

Critically, this picture is not inconsistent with the idea that people in general, or symbolic capitalists in particular, can make genuine sacrifices and do actual good.

When I say that people typically perceive, reason about, and describe the world in ways that help us advance our interests, for example, it’s critical to note that interests needn’t (and shouldn’t) be understood in a purely materialistic or individualistic way. Chapter 1 stresses that, in addition to material interests, people have ideal interests that often supervene and supersede material concerns. In pursuit of these ideal interests, people regularly incur risks and make sacrifices in the name of communities, causes, institutions, and the Divine.

Moreover, pace classical economics, the individual is not the scale at which people tend to evaluate their interests. At the minimum, tend to incorporate those they view as “kin” into their considerations. Indeed, as economist Samuel Bowles powerfully illustrates, capitalism wouldn’t even work if people actually were driven first and foremost by the maximization of material interests, understood in starkly individualist terms. Those who do narrowly understand and doggedly pursue their interests in starkly individualistic terms are rare and often described as “sociopaths” or “psychopaths.”

Put simply, people do tend to perceive, think and talk in ways that help them advance their interests and further their goals. However, people’s goals and interests are not always (or primarily) individualistic or materialistic. The problem the book focuses on is not “human nature” but, rather, the specific and unusual ways that symbolic capitalists in particular tend to conceptualize and prioritize various interests and goals.

Symbolic capitalists are unusual in many respects. For one thing, we do tend to think in more individualistic terms than most people. We’re more risk averse than others too. As a function of these characteristics, we’re less likely than most to put our status, resources and aspirations “on the line” in the service of the causes, organizations and people we identify with – even as we often call on others to make immense sacrifices on behalf of the same. But, again, this isn’t because of “human nature” writ large. It’s a problem of culture. It’s a product of how symbolic economy institutions select, develop and incentivize people. And the good news is, cultures are things that can be changed (in fact, all cultures do change constantly).

Ultimately, the message of the book is not bleak. It could even be read as optimistic. A central argument of We Have Never Been Woke is that symbolic capitalists do, in fact, have a lot of influence and agency. It is within our power to exercise our resources, will, and clout in different ways than we have. And how we ultimately choose to behave is of significant practical importance to others – including and especially the genuinely marginalized, disadvantaged and vulnerable in society. Empirically speaking, the book argues, symbolic capitalists cannot realize their explicit social objectives while continuing to be elitists, careerists and cowards. This is the source of a moral and political dilemma: symbolic capitalists have to make choices about what is most important to us.

Critically, what people value is something social scientists can readily observe “from the outside.” You don’t have to see into others’ hearts and minds to perceive it. And you can ignore their pious expressions too. You find out what matters to people by looking at what they do: How do they structure their lives and pattern their relationships? How do they operate within their institutions and communities? How do they allocate finite time, energy and resources? These are all things symbolic capitalists have the capacity to change. Whether we have the will remains to be seen.

The book was ultimately published in a very different moment than the one it was conceived and written in. Are you worried that, in the current milieu, the criticisms of the book will be utilized by “bad actors” in the service of ignoble ends? Is this the right moment to have the conversations the book is trying to start? Is the book a distraction from the most important problems we need to address right now?

The short answers to these questions are “No,” “Yes,” and “No” respectively. I unpack these answers at length in a previous post here.

Isn’t the “real” problem for social justice that Trump, the Republicans, and their “deplorable" supporters, and their greedy financial backers keep blocking Democrats/ liberals/ symbolic capitalists from achieving our laudable goals?

In fact, Republicans are demonstrably not the primary obstacle to achieving our professed social justice goals. The problem isn’t that symbolic capitalists lack political power, it’s that they lack sufficient political will. And in particular, we lack the will to take actions that require us to put our money where our mouth is — to risk or sacrifice anything ourselves, to adjust our own lifestyles and aspirations, and those of our children and loved ones. On many levels, as I demonstrate in the book, partisan politics is a very poor lens for understanding how social problems come about and persist, who benefits from them (and how), and what can be done (and by whom) to mitigate these issues.

Your book is very critical of symbolic capitalists and their dominant ideologies. Isn’t there good symbolic capitalists have done? Aren’t their virtues to our social justice orientations?

I wrote a separate addressing these questions here.

How does your analysis of “symbolic capitalists” relate to previous work on, say, the “new class,” the “professional managerial class” or the “creative class”? Why didn’t you use one of those terms?

Although We Have Never Been Woke is an academic text, it was designed to have crossover appeal, and we worked to get it as lean as possible, so I wasn’t able to include a literature review in the book that would’ve gone into this. But I wrote a quick lit review in the original draft that I previously published on this Substack here. I might also recommend this follow-up introducing readers to the symbolic economy.

But the short answer to this question is that, although these other authors drew the lines a little differently in terms of who is “in” and who is “out,” for my purposes symbolic capitalists can be used more-or-less interchangeably with terms like “PMC” or “symbolic analysts,” or “intelligentsia” or “liberal elite.” These are all terms that, loosely, point towards the same elite constellation.

I loved that this post was very challenging to me, a fellow symbolic capitalist, denying easy answers or validation. And I like that you explained why you're doing that here and in your book. I'm getting tired of the "easy" answers offered in the liberal-progressive discourse. I will be supporting your own work as a symbolic capitalist by buying your book, alongside a healthy sense of irony!

I would add that there's potentially a feasible, non-self-abnegating path out of this dilemma hinted at in the post and the book: "people have ideal interests that often supervene and supersede material concerns" and "the individual is not the scale at which people tend to evaluate their interests." Interests are, indeed, very socially mediated, which means that we can change each other:

I've seen that by moving between different cultures in my adult life. I'm American, but live in Sweden now, a similarly wealthy, Western, individualist, culturally-Christian, consumer-capitalist society. It's the same, but different. Here in Sweden, I don't feel the same "I got mine!" attitude that is so pervasive in the United States. I still feel shame here for being a little too on-the-nose about bouts of indulgent selfishness or conspicuous consumption. I receive ambient pressure to be thrifty, scrupulous, and conscientious in a way that feels very contra Trump Era America. Swedes have their blind spots toward inequality and their own space at the top of the hierarchy of symbolic capitalism and globalization, of course, but there's something a little more hesitant and tasteful about their ambivalence toward the nastiness underneath their society's calm. And it's not just "virtue signaling" or "liberal guilt," this social pressure toward conscience does have some real benefits: Swedes generally have at markedly lower environmental impact, enjoy more social equality, and are far less violent than Americans are. There was a time not so long ago, also, where the symbolic capitalists of Sweden took real risks in advocating for a better society for all.

And this "well-behaved" ambivalence toward one's own inner capacity for craven-ness and advantageous position near the output of a societal wealth pump is not that alien to American culture, really: it's way Americans used to feel, at least if my c. 1910s grandparents were any guide. So, what's in our interests can change in time, as well as in space. Obviously, as lovely as they were, my grandparents also profited handsomely from a society that was rather barbaric at root, whether they were self-aware about it or not. So let me not excuse them (or myself). It's just to say that it's possible to be *better* if not fully and purely *good.*