A Graveyard of Bad Election Narratives

All the prominent but obviously false narratives about the 2024 election prepared for burial in one convenient post.

Most scholars and journalists are on the blue line of political charts. Consequently, whenever analysts want to explain something they view as “bad,” they tend to focus exclusively on the red line people – and they explain the aforementioned “bad” outcomes in terms of deficits (ignorance, lack of cognitive sophistication, lack of empathy) or pathologies (racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, authoritarianism) that purportedly hold among “those people” who have the “wrong” political lean.1

Donald Trump’s reelection is a definite case of something most scholars and journalists view as “bad.” And, per usual, narratives attributing the loss to malign opponents of Harris are already being widely circulated. Many of the most popular tales have obvious confounds. However, this has not inhibited their uptake much, because many who circulate these narratives seem less interested in engaging with empirical details than in telling comforting stories to folks hungry to hear them.

For others, who are genuinely interested in the facts of what went wrong for Democrats this cycle, this post is designed to rule out what wasn’t the problem. Let’s start with the elephants in the room:

Racism?

Harris is black. Trump says racist stuff on the regular. Trump won. It must be because of racism, right? Open and shut case.

Not so much.

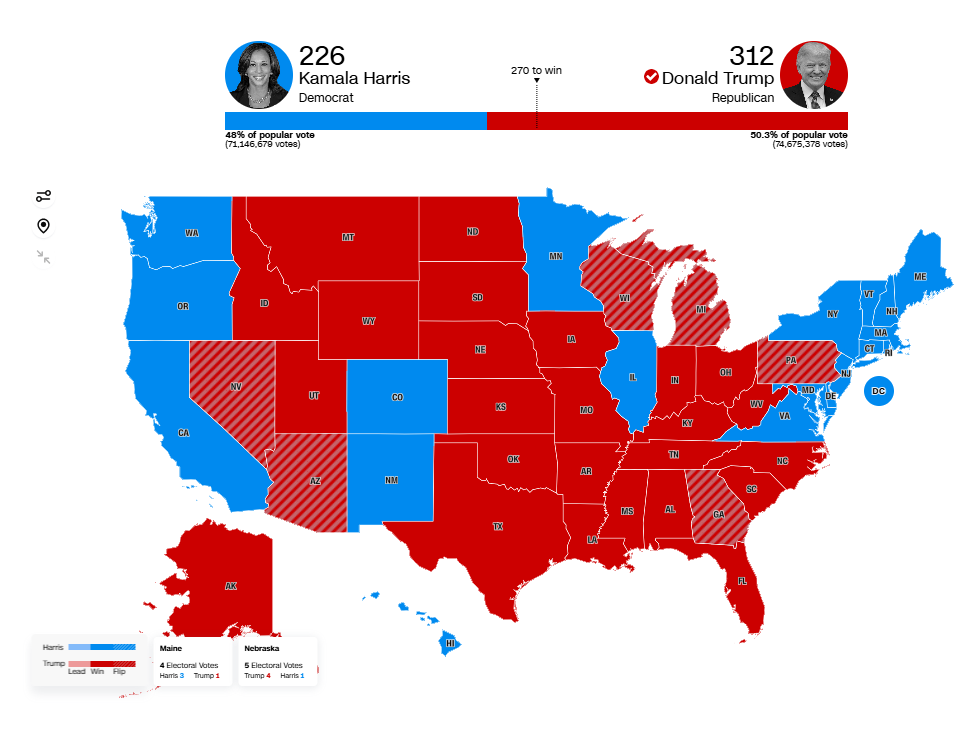

For one thing, the GOP has been doing worse with white voters for every single cycle that Trump has been on the ballot, from 2016 through 2024. And there’s tons of evidence that Trump’s racialized language has been a major driver of this trend – it’s been a drag on his support among whites rather than serving as the key to his success.

Meanwhile, Harris did quite well with whites in this cycle. She outperformed Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden with white voters. The only Democrat who put up comparable numbers with whites over the last couple decades was, incidentally, another black person: Barack Obama in 2008. Exactly what one would expect if racism was driving electoral outcomes, am I right?

What’s more, the whites who shifted most towards the Democrats over the course of Trump’s tenure have been white men. It was dramatic shifts among white men that allowed Biden and Harris to win in 2020 even as they underperformed Hillary Clinton with black, Hispanic and Asian voters, and women of all racial blocs.

In 2024, white men voted for Harris/ Walz the same levels they voted for Biden / Harris in 2020. And this cycle, white women also moved towards the Democratic Party:

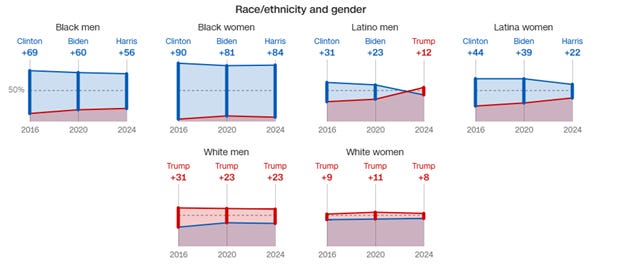

The problem Kamala faced was not with whites. Democrats had more than enough white votes to win the general election. Going all the way back to 1972, there have only been a few cycles where Democrats won a larger share of the white vote than they did in 2024 (namely 1976, 1996, 2000 and 2008).

If whites across gender lines shifted towards the Democrats this cycle (compared to last), and if Democrats’ performance with whites was objectively solid (compared to every other year on record), then why did Harris lose so decisively? Because Democrats’ gains with whites in 2024 were more than offset by losses among non-whites — men and women alike.

This is not a new trend either: Democrats have been bleeding non-white voters in every midterm and general election since 2010. Democrats’ gains in 2018? Driven by whites, despite weak showing from minorities. The “red wave” that never materialized in 2022? Thank the whites — minority shifts helped the GOP take the House. This time, however, the whites couldn’t insulate Democrats from the levels of attrition they experienced with minority voters.

Let’s start by exploring the black vote:

Kamala has never enjoyed strong support with black people. In the 2020 primaries, she was rarely the top choice of even 5 percent of black respondents in polls. She typically trailed not just behind Joe Biden, but Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and often other candidates too. Because Harris had no real base of support, she ended up dropping out before a single vote was cast. Nonetheless, Biden appointed Kamala as his VP, apparently believing this would improve Democrats’ numbers with black people and women. Instead, they did worse in 2020 than in 2016 with women, black people, and black women in particular (ditto with Asians, including Asian women). Harris added nothing to the ticket.

This cycle proved 2020 was not a fluke: in 2024, Democrats had their lowest performance with black voters in roughly a half-century. Much attention has been paid to black men in generating this outcome. However, Harris didn’t do particularly well with black women either. She underperformed Hillary Clinton with these constituents who, herself, underperformed Barack Obama. Put another way, going back 16 years and five elections, the only ticket that did worse with black women than Harris/ Walz in 2024 was Biden/ Harris in 2020.

Black people across the board were lukewarm on Harris, this cycle and last. And not just black dudes.

For Hispanics, a similar picture holds. It’s been more than 50 years since Democrats performed as poorly with Hispanics as they did in 2024. There has been a lot of focus on Hispanic men in driving this outcome, but the trend was very strong among Hispanic women as well. Latinas shifted 17 percentage points towards the GOP this cycle relative to 2020. As compared to 2016, Democrats’ margin with Hispanic women has been halved over the last two elections.

As with African Americans, to the extent that analysts are focused on men, they’re missing what’s really going on this cycle. Non-whites across gender lines were cooler on Harris than virtually any other Democratic candidate in modern political history.

The CNN graphic I shared above doesn’t include Asians for some reason, but the same shifts were evident among Asian American voters as well, for the reference.

Across the board, Harris and Walz improved their numbers with whites – men and women alike. Democrats lost because everyone except for whites moved in the direction of Donald Trump this cycle.

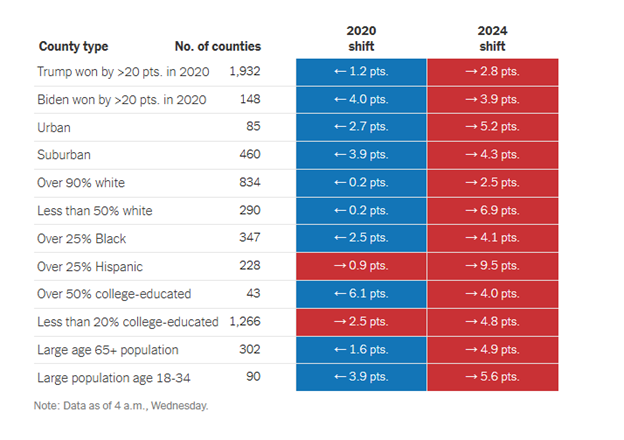

You can see this pattern in pre-election polling and exit-polling. In fact, let’s skip attitudinal measures altogether and analyze the magnitude of vote shifts by country relative to the demographics of those counties. What do we see? One thing that jumps out is that “minority-majority” counties and places where more than a quarter of the population is black or Hispanic shifted towards the GOP at multiple times the rates of regions that are almost entirely white:

Again, the whites are not “the problem” (to the extent that one views Trump’s election as a problem). Nor is the typical Republican a seething racist, with growing animosity against minorities driving their support of Trump. Instead, by most empirical measures, Republicans have been growing more “progressive” on issues tied to race for years now — before, during and after the Trump presidency. This is true even when we restrict the analysis to whites.

Across the board, it’s impossible to understand the trends among whites or non-whites from within the dominant racialized framework about Trump and his supporters. The narrative didn’t explained 2016 well. It has done an even worse job on every cycle since. Folks need to let it go. The racism some seem to fervently desire simply isn’t apparent in folks’ actual voting patterns (and this is a good thing).

Sexism?

Trump is known for his derogatory words and behaviors towards women. He defeated a woman, Hillary Clinton, in 2016. He lost to a man, Joe Biden, in 2020. He then bested yet another woman, Kamala Harris, in 2024. Misogyny must be driving these outcomes, right? It must be that Americans, especially men, just can’t stand the idea of a female president.

Not really.

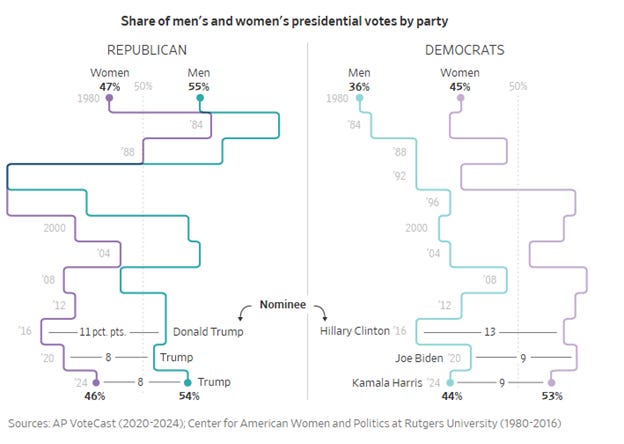

Trump did do better in this cycle with men than in any of his previous campaigns. However, his 55 percent vote share among men was hardly unprecedented: Republicans Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and George W. Bush all captured the same share of the male vote or higher. Going back 50 years, there have only been a few cycles when Republicans failed to get more than half of the male vote — and they lost the election every time that happened.

Critically, until somewhat recently, the voting patterns of men and women were not that different. Whoever got the lion’s share of the male vote tended to win the female vote too. This changed after 1996. And it didn’t change because men suddenly grew more Republican (they didn’t). It changed because women shifted aggressively towards the Democratic Party in the mid-90s, and consistently gave Democrats around 54 percent of their vote for every cycle since, irrespective of who was at the top of the ticket or what the pressing issues of the day were.

There have been races since 1996 where the Democrats have won a plurality of the male vote (2008). There has been no presidential election of the past 30 years where a Republican got a plurality, let alone a majority, of the female vote. Put another way, women are more staunchly Democratic than men are staunchly Republican. Put still another way: men are more likely to be swing voters than women.

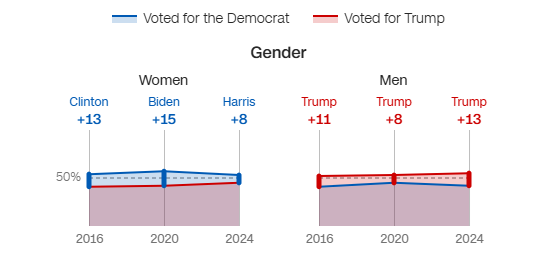

In 2016, as a result of these swings, the gender gap between men and women was extraordinarily high. Going into 2024, there was an expectation that the gap might grow bigger still. In fact, it was smaller. The gender divide between men and women this cycle was roughly identical to the last (both reduced from 2016).

You might wonder how that’s possible given that I just said Trump did better in 2024 than he ever had with men. It’s because he performed better than ever with women this cycle too:

Between 2016 and 2024, men shifted 2 percentage points towards the GOP. Women shifted 5 percentage points away from the Democratic Party over that same period – more than twice as much! Yet, the post-election focus has been overwhelmingly on men for some reason.

So let me put it bluntly: Democrats lost in 2024 because Harris performed extremely poorly with women. Going all the way back to 1996 (when the partisan gender divide kicked into high gear), there has been only one Democrat who performed worse with women than Kamala did: John Kerry in 2004.

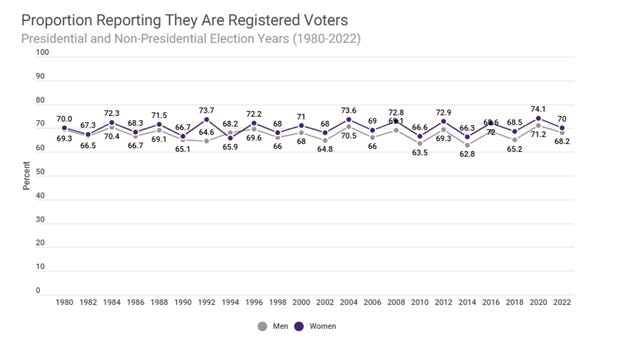

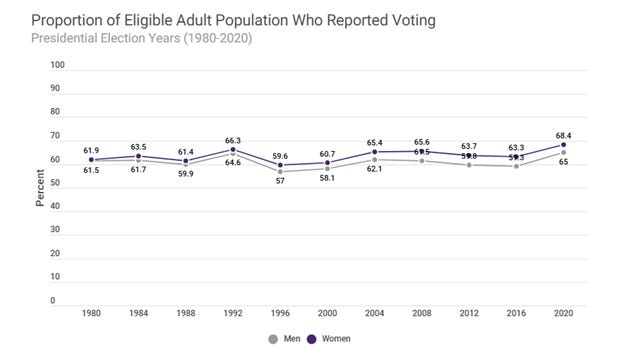

And it is Democrats’ performance with women that drove the ultimate outcome. In fact, women have been the primary deciders for virtually all U.S. presidential contests since 1976. Women comprise a majority of the U.S. adult population. Over the last four decades, they have also consistently registered to vote at higher rates than men.

And among registered voters, women have turned out to the polls at higher rates than men in every single presidential cycle over the same period.

As a consequence, women have typically made up around 52 percent of the folks who cast ballots in a given cycle, while men have comprised roughly 48 percent. But guess whose votes are the overwhelming focus of scholarly research and journalistic reporting?

Despite the fact that the female vote is objectively more important than the male vote, fancy nerds and talking heads tend to ignore how women exercise their agency in elections… especially when races go the “wrong” way. Even feminist scholars (perhaps especially feminist scholars) tend to focus on men – on finding ways to explain voting outcomes in terms of sexism, misogyny, and so on among men– while neglecting the extent to which women drive many of the electoral outcomes they decry.

This tendency is especially ironic in cycles like 2016 and 2024, where a woman was at the top of the ticket. It seems more important than ever to focus on how female voters exercised their agency in support of these historic candidates (or not). But this is typically not the priority.

I suspect the reason analysts decline to analyze female trendlines is because the empirical realities are inconvenient for their preferred narratives: in both cycles, the reason the Democrats lost was because they got lukewarm support from women. Harris did even worse than Clinton in this regard (dethroning Hillary for the worst Democratic performance among female voters outside of John Kerry).

Here one might think, “Okay. Well, the reason Kamala did especially poorly with women was because older voters just couldn’t handle someone like her. She was too “brat.” Too progressive. Too young. Too brown.”

There are two obvious problems with this narrative. First, again, Harris outperformed Hillary with white women but saw anemic support from black, Hispanic and Asian women relative to Clinton (even though Hillary’s own numbers with these groups were markedly lower than Barack Obama’s). Harris’ ethnicity wasn’t an obstacle to her support.

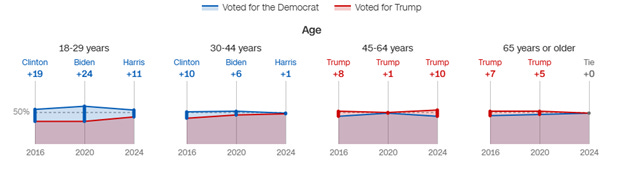

The outcome wasn’t caused by the “olds” either. Quite the opposite:

The biggest shifts that occurred over the last two cycles have been with voters under 44. Democrats have been consistently losing ground with Americans 30-44 since 2016. They’ve shifted 9 percentage points towards the GOP since Trump’s first run. Democrats’ margins with Americans under 30 shifted even more. Their margins fell by more than half since 2020. Overall, these voters shifted 7 percentage points towards the GOP since the first time Trump was on the ballot.

For contrast, Americans from 45 – 64 shifted a mere 2 percentage points towards the GOP over this same time period. And Americans 65 and older shifted 7 percentage points towards the Democrats.

Put simply, it was shifts among young and non-white women – the very constituents who were supposed to ensure Kamala’s victory – who instead helped usher Trump back into the White House.

Why did Americans vote the way they did? It demonstrably wasn’t because U.S. voters are hesitant about women in leadership. They’re not.

In fact, even as Kamala’s candidacy went down in flames, women did pretty well at the ballot box this year. For example, as a result of this election cycle, there will be a record number of female governors in the U.S. in 2025. The 119th Congress will be just two seats away from the all-time record for female representation in the legislature. 18 non-incumbent women won House seats; 107 female House incumbents won reelection. 3 non-incumbent women won Senate seats. There were many firsts this cycle as well, including the first transgender woman elected to U.S. Congress.

Put simply: voters didn’t seem to have any problem electing women this cycle. They just didn’t respond well to the specific woman that Democrats put at the top of their presidential ticket. And there was a lot not to like! (more on that soon).

Finally, it should be emphasized, there is a sense in which gender differences are completely overblown in most cycles, including this one. There was a non-trivial gap between men and women in 2024 — albeit not record-breaking. And even the record-setting gap was less than one might assume. There has never been a presidential election in U.S. history where even 60 percent of men voted one way while a similar share of women voted the other. Let alone anything like a 70/30 gender split, or an 80/20 divide. It’s just not the case that men homogenously vote Republican. Nor is it the case that women overwhelmingly vote Democrat.

In this race, nearly half of women voted for Trump, while slightly more than half cast ballots for Harris. On the male side, although most voted for Trump, nearly half pulled the lever for Harris. In fact, going back to 1980, there have only been a handful of races where Democrats did better with men than they did in 2024 (namely: Joe Biden last cycle, both contests with Barack Obama, and Bill Clinton’s 1996 reelection bid). Kamala’s performance with men was solid. It was her performance with women that destroyed her prospects.

Across the board, the level of political overlap between men and women is consistently far larger than the differences between them. This is often lost in The Discourse, but it’s important to bear in mind. Again, Trump didn’t just rack up his personal best numbers with men this cycle, he did the same with women. And again, given that white women trended towards the Democratic Party this cycle, the gains he made among women were entirely a product of shifts among non-whites — particularly Asian and Hispanic women.

Revolt of the Elites?

Donald Trump is a billionaire. He was staunchly supported by Elon Musk, the richest person on planet Earth. Trump won. This must mean that rich and powerful people essentially bought this election — and at the expense of the preferences of “normie” voters — right?

In fact, Trump and Musk weren’t the only billionaires rooting for the GOP this cycle. According to Forbes, more than 50 other billionaires also threw their weight behind Trump. So far so good for the preferred narrative. But here’s the twist: even more billionaires — 83 to be precise — supported the Democratic nominee. Kamala had 60 percent more billionaire backers than Donald Trump did. And billionaires like Oprah and Mark Cuban hit the campaign trail serving as surrogates for Harris in much the same way as Musk supported Trump.

At first glance, looking at contribution data, it seems like there might be a way to redeem “the narrative” because, even though the GOP had fewer billionaires backing them, at first glance it could seem like Trump’s billionaire buddies made bigger bets. In terms of disclosed donations, for instance, Axios reports that significantly more billionaire money went to Trump than Harris. But of course, disclosed donations are just the tip of the iceberg of money in politics.

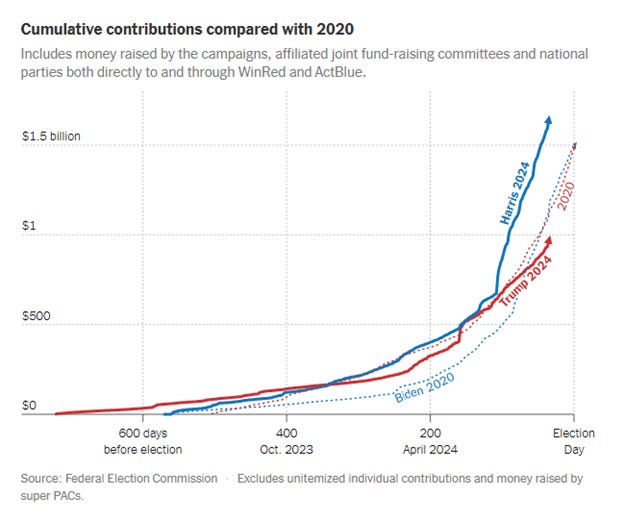

In terms of total dollars raised and spent over the course of this cycle, it wasn’t even close… because the Democrats brought in much more money than the GOP – largely through millionaires, billionaires, multinational corporation, and “dark money” PACs. As OpenSecrets reports, 2024 was the most expensive election in American history (adjusted for inflation). And at both the presidential or Congressional levels, it was Democrat-aligned PACs that dominated in terms of fundraising and spending. This held in the last cycle as well: Democrats more than twice as much “dark money” as Trump in 2020.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton raised twice as much as Donald Trump (with a much higher share of her donations coming from PACs, bundlers, large gifts, etc. as compared to her opponent, who was much more heavily funded by grassroots donations). Despite this much larger war chest, she lost the election. This cycle, Democrats once again raised roughly twice as much money as their opponents overall, with the same basic outcome.

In the months after Joe Biden dropped out, Democrats raised more than $1 billion – more than three times as much as Republicans brought in over the same period – largely thanks to enthusiastic support for Kamala Harris within Wall Street, Silicon Valley and Big Law.

The Democrats didn’t just outraise their opponents, they burned through raised income much faster too. As a consequence, despite setting fundraising records, Harris’ campaign is purportedly more than $20 million in debt.

How’d this happen? For one, there was tons of financial mismanagement – with millions paid to celebrities in exchange for appearances and endorsements. In one striking case, more than $100k was spent building a custom studio for one specific podcast (that was never reused).

But the Harris campaign also burned through tons of money in conventional ways. With respect to advertising, for instance, Democrats outspent Republicans in nearly every swing state (excepting Ohio, Florida and Texas) – often by huge margins — and they still lost every single one of these contests. It turns out, it’s actually hard to simply buy elections. Good news for democracy, bad news for Democrats this cycle.

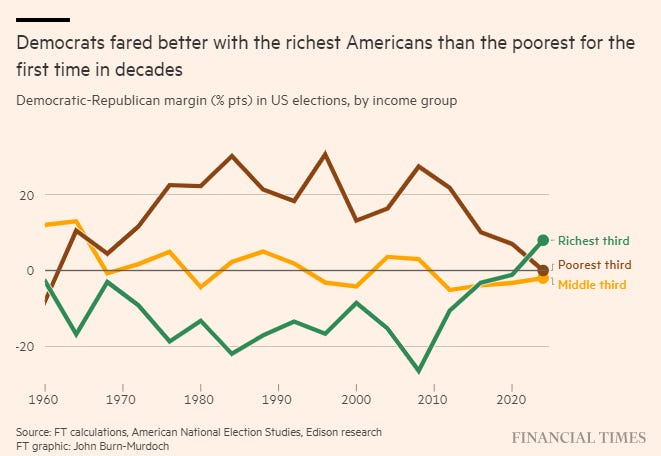

When we shift our gaze away from donations to look at how people across class lines cast their votes, the picture is much the same. Wealthy voters shifted even further towards Democrats this cycle than they did in 2020 – a significant feat given how heavily these voters were consolidated into the Democratic Party over the course of the last decade.

Harris was the clear choice for voters with six-figure salaries or higher, while Trump won with people earning less than $50,00 per year. In fact, Democrats performed better with affluent Americans than with any other income bloc.

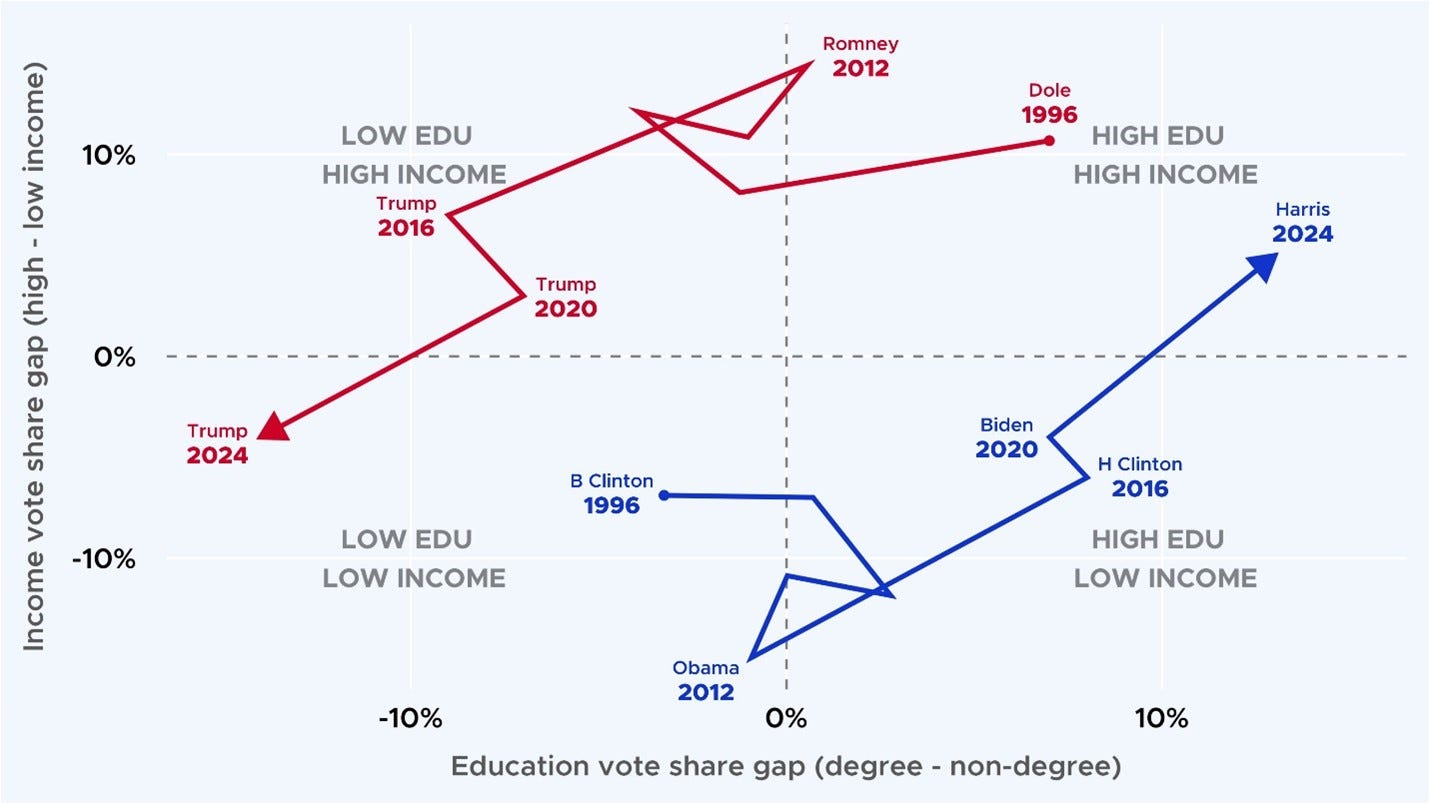

When we look at education and income simultaneously, it becomes even clearer that Democrats have become the party of elites. The class composition of the Democratic and Republican parties has basically flipped over the last 30 years:

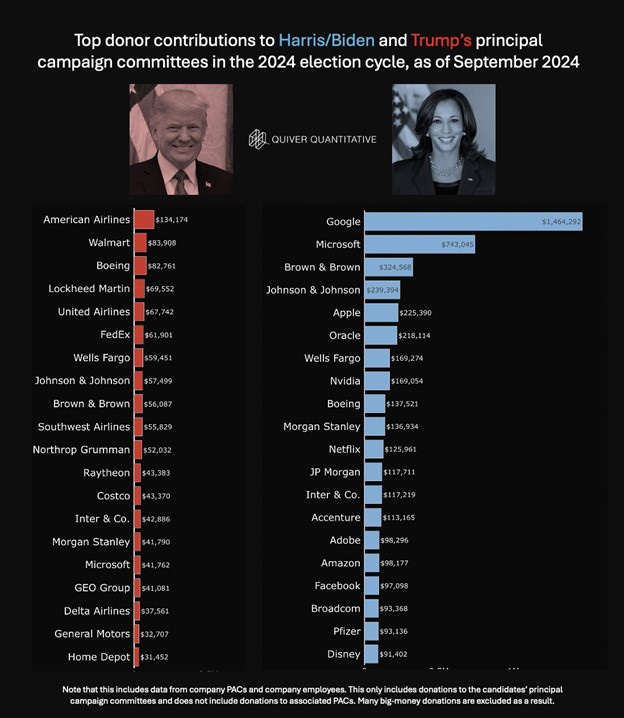

We see a similar pattern when we look at which workers and employers (company PACs) supported each candidate. Trump was most heavily supported by folks tied to shipping and logistics companies (including airlines), retail stores, and defense contractors. That is, people oriented towards providing physical goods and services. Harris was supported primarily by the symbolic professions: big tech, media and entertainment companies, pharmaceutical brands, and finance.

Here again, among companies with the highest employee donations and PAC support, the overall contributions were much higher for Democrats than Republicans. Even for businesses that ended up on both candidates’ lists (typically those tied to banking and finance), the wealth was not spread even close to evenly. Instead, donations to Democrats tended to be multiple times higher than contributions to Republicans.

Augmenting this data, one could directly observe tensions between Democrats’ “for the people” narratives and their actual base of support playing out in real time at the Democratic National Convention: literally right after Bernie Sanders (himself, a multimillionaire) gave a talk condemning corporate greed, oligarchs, and the corrosive influence of money on politics, billionaire J.B. Pritzker took to the stage — the richest politician currently serving in office — and promptly bragged about how wealthy he was to enthusiastic cheers (unfortunately, neither a joke nor an exaggeration) before talking about his reasons for supporting Kamala Harris. It was a wild night.

All said, if we understand this election to be a contest between “elites” and everyone else, we would have to conclude two things:

The Democrats are the “elite” party (they had more billionaires and raised far more money overall, including more “dark money” ; they were the preferred party of affluent voters; they were the preferred party of highly-educated voters; they were the preferred party of professionals and their employers), and

Despite throwing unprecedented amounts of money into the election to support their preferred candidate, the dominant “elite” faction in the U.S. lost. Right or wrong, voters overruled the lion’s share of American elites in order to reinstall Trump to the White House.

This election was not a race where billionaires outspent their opponents and won. If anyone tried to simply spend their way to victory this cycle, it was Democrats. And they were unsuccessful.

Spoiler Alert?

When other narratives seem to fail, analysts love to scapegoat third parties for electoral outcomes they don’t approve of.

I say “scapegoat” because, of course, the only reason third-party candidates are able to “steal” votes from the major parties is because their opponents aren’t satisfactorily addressing constituents’ core concerns. Major parties could try to adjust their messaging and platform to win these voters (back), but instead they tend to blame the Greens or Libertarians for offering up a more attractive alternative vision. In the absence of these third-party options, it should be noted, many of these voters would likely just stay home rather than vote for either of the major-party candidates. The whole “spoiler” narrative is deeply flawed from the jump.

For the moment, let’s set these realities to the side. A deeper problem with blaming, say, Jill Stein or Cornel West for the 2024 electoral outcome is that there were only two states in the nation where the margins between Trump and Harris were close enough such that, if all third-party voters cast ballots for Harris instead, it would have flipped the state: Michigan (worth 15 electoral votes) and Wisconsin (worth 10 electoral votes).

Critically, many Michigan voters who cast ballots for third parties were intractably set against Biden/ Harris due to their Middle East policy. If Democrats changed nothing about their positions on the region, but these voters were compelled to vote for one of the two major party candidates, many would have broken for Trump, possibly running up his margins even further rather than helping flip the state. In both states, voters who cast ballots for RFK Jr. or Libertarian candidate Chase Oliver would likely have voted largely Republican if their first choice was not on the ballot, negating many of the votes for West or Stein that might have otherwise gone to Harris (if these voters cast ballots at all in a strictly two-party race).

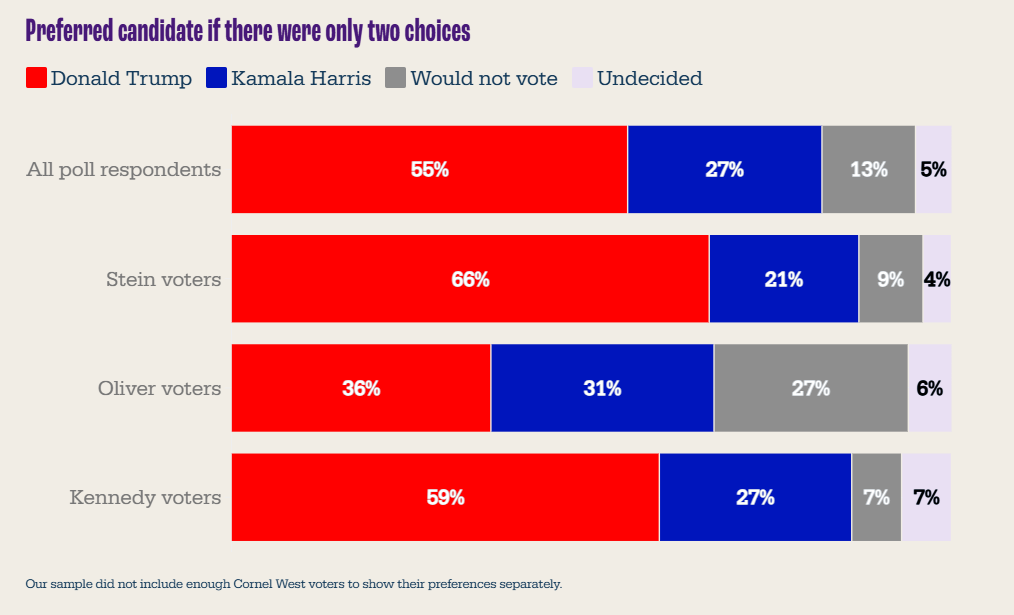

Indeed, if we zoom out to the national level, a post-election survey of third-party voters by Fair Vote found that in a two-party race, most third-party voters would have still voted — but they would have case ballots for Trump:

This is even true for Jill Stein voters — in fact, it’s truer for them than for anyone else (which makes sense because many voted for Stein as a protest vote against Biden and Harris. And they still would have probably cast a protest vote in a two-party race — they’d just have voted Republican instead of Green to accomplish this goal).

Put another way, had Jill Stein abstained from the race, Trump’s margins nationally, and perhaps in swing states like Michigan, would likely have been larger, not smaller. Democrats should be thanking third-parties in this instance, rather than condemning them.

But again, for the sake of argument, let’s just wave away these pesky details, assume that all third-party voters would have gone for Democrats in a two-party race, allocate all third-party vote to Harris and, as a consequence, give her the states of Wisconsin and Michigan. What does that change? Absolutely nothing.

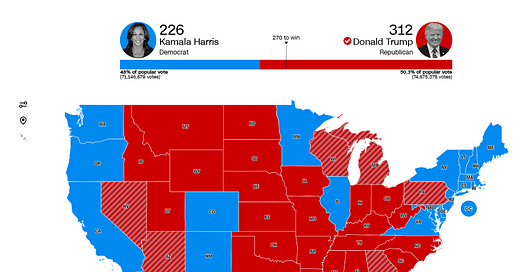

If Harris received 100% of all the third-party votes nationwide, she’d have ended up with 251 electoral votes (instead of 226), but she’d still have lost the election. Under this scenario, Trump would still win 287 electoral votes (instead of 312) – but you only need 270 to win the White House. If all third party votes went to Harris (even the ballots cast for right-aligned candidates like Oliver and RFK), Harris would have narrowly won the popular vote, but still lost the electoral college. In a more plausible scenario where we simply migrated Stein and West voters, she would have still lost both the electoral college and the popular vote.

Democratic strategist James Carville helpfully explained that when confronted with the fact that Harris lost by less than three million votes, it’s tempting to think things like, “Well, James, it wasn’t a landslide. We only lost by a point and a half.” He continues that, while this is true, it’s also true that Democrats “won by four and a half the last time, meaning the overall vote margin shifted a lot between this cycle and last — a “six point turnaround in American politics is a seal out. It’s like losing a football game 35 to 10. You’re not close.”

Put simply, third parties didn’t “spoil” this race for Harris. She lost the race cleanly and decisively – both at the electoral college and popular vote levels – with or without third parties.

Turnout Troubles?

Elections are not won by overall public opinion but, rather, by the folks who show up to vote on election day. The subset of people who actually cast ballots tend to be systematically different from those who don’t: they are more likely to be white, to be older, to be female, to have higher incomes, more education, and to live in more urban areas.

This cycle, Trump notched 3 million more votes than he did in 2020 (when he earned the second-highest number of ballots cast for any presidential candidate in U.S. history, surpassed only by Joe Biden who ran against him in that same year). However, Kamala Harris netted 6.3 million fewer votes than Joe Biden did last cycle.

Of course, some of this is because many people who voted for Biden in 2020 shifted to Trump for 2024. However, that could only explain roughly half of the drop off at most. At least three million other Americans who voted for Biden and Harris last cycle just chose to sit this election out. In fact, the number of people who sat out is larger than the popular vote difference between Trump and Harris. It is perhaps tempting to think that, if only those people had voted this round, the race would have gone the other way. However, such an inference would be deeply misguided:

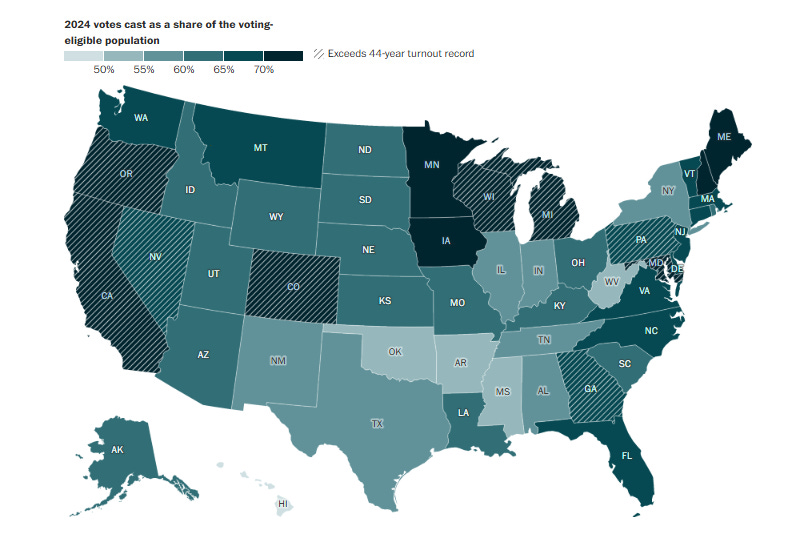

First, while overall turnout was down slightly from 2020 this cycle, this was not the case in the states that decided the election. Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin and Michigan all had record voter turnout. They had more folks cast ballots in 2024 than last round. And Harris lost all of these swing states nonetheless.

The decreases in turnout were largely concentrated in “safe” states for one party or another – among folks who (correctly) perceived that their vote wouldn’t change the outcome of the race, and who were apparently not passionate enough about their preferred candidate to cast a vote for purely expressive purposes. Mobilizing these voters to the ballot box would not have meaningfully changed the Electoral College outcome even if they voted the same way in 2024 as they did in 2020. But of course, many of them would not have voted the same way.

There’s no reason to believe that voters who sat this cycle out would have gone for Harris at similar margins as the last election instead of trending towards the right like the rest of the country. In fact, there are reasons to think heightened turnout would have been counterproductive for Democrats:

In recent years, low propensity (less urban, less educated, less affluent, less old, less white, less female) voters have increasingly drifted towards the Republican Party, while high-propensity voters shifted the other way. Hence, Democrats have been increasingly overperforming (relative to polls) in races where turnout is low, such as midterms and special elections — while high-turnout races have often seen Republicans do better than polling predicted.

At present, neither party’s electoral strategies have fully caught up to the new reality.

Democrats keep trying to “rock the vote” and expand voter access under a mistaken belief that low-propensity voters are “on their side.” We saw the fruits of this miscalculation in 2020: Democrats invested tons of resources into areas of swing states with heavy concentrations of non-white voters. Those voters were, in fact, mobilized — and the areas where these low-propensity voters went to the polls were also the areas of those states that shifted the most towards the GOP.

Meanwhile, Republicans keep operating under the assumption that broad-based turnout is a threat. And so, they have tried to complicate voting through Voter ID laws and discouraging early or mail-in voting – moves which may have actually cost Trump the election in 2020. Had still more low-propensity voters cast ballots in key states, it probably would have been to his benefit.

As it stands, in 2024, turnout among high-propensity voters was slightly higher than last cycle. Democrats mobilized the people who were most likely to vote for them. Almost all of the declines in turnout were among electoral blocs that:

Are less likely to vote in general, and

Have shifted towards the GOP in recent cycles, including this one

(e.g. Black and Hispanic voters, less educated voters and less affluent voters).

If more of these folks had been mobilized this cycle, Trump’s popular vote victory likely would have grown larger, not smaller – even as the Electoral College outcome probably would have gone unchanged. If anything, with higher turnout, Republicans might have been able to flip New Hampshire (the state Democrats won by the smallest margin), expanding Trump’s electoral lead even further.

In any event, Harris did not lose because of low turnout. A world where turnout this cycle met or exceeded 2020 levels would probably be a world where Kamala performed even worse.

Then tell me what happened already!

We can see from the preceding discussion that the most prominent narratives for why Harris lost seem to be clearly wrong. She was not undone by racism or sexism. Elites didn’t buy the election. Third parties didn’t “spoil” the race. Higher turnout wouldn’t have helped her.

Here a reader may reasonably interject: “If The Discourse is so misguided about why things went the way they did, how do you explain the electoral outcome?”

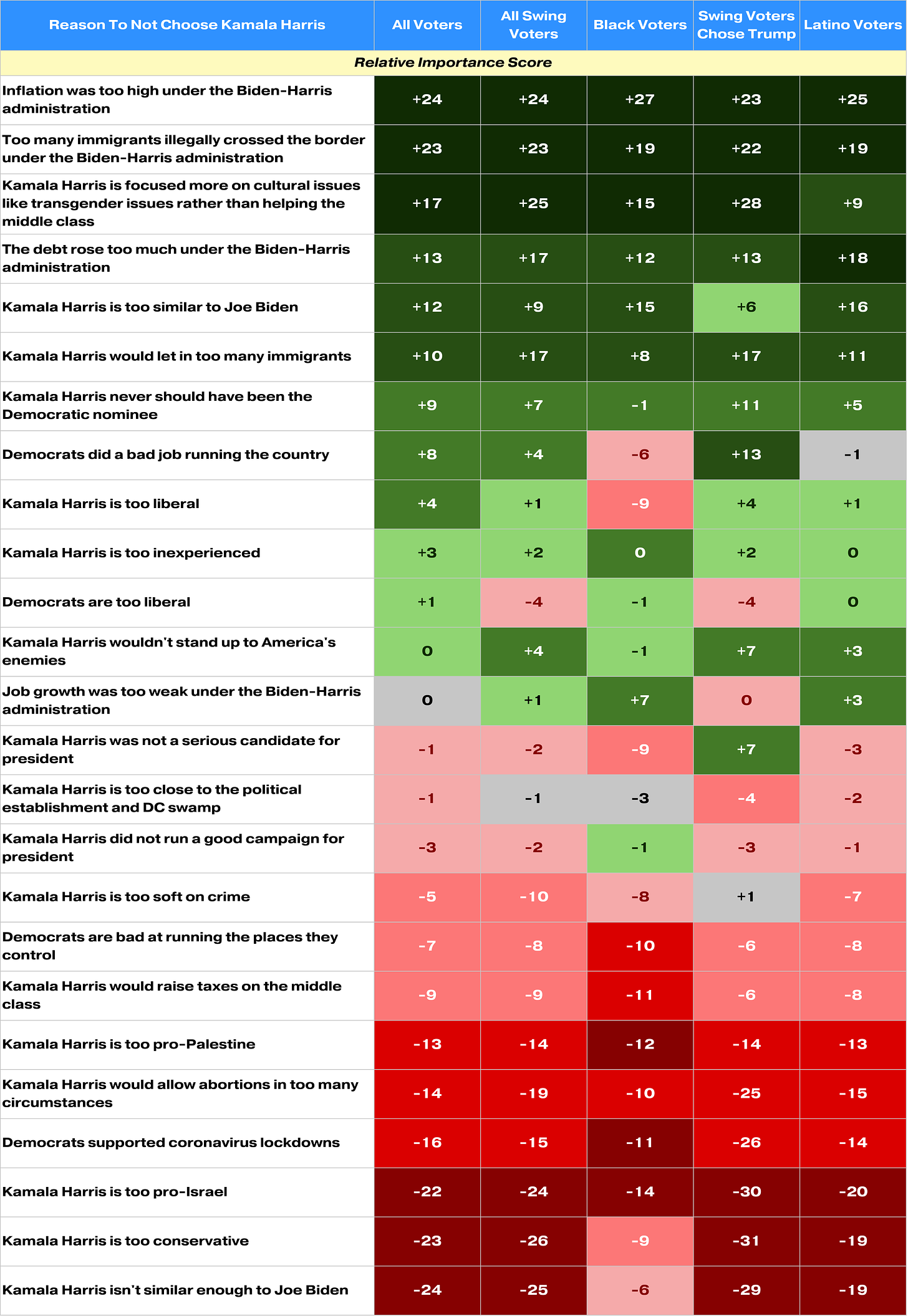

If you look at voters’ expressed opinions, it seems like there were three core factors: inflation, immigration, and alienation from cultural liberalism.

I don’t think voters are wrong about what their core concerns were. That is, I think people were genuinely concerned about inflation (even though inflation was consistently declining for the two years leading up to the election), etc. However, it also seems likely that, even if these weren’t the core issues voters focused on, the trendlines would have continued the same way. Maybe the attrition from some groups would have been a little more or a little less. Maybe Democrats would have squeaked out a narrow win or lost in a landslide. But either way, Democrats probably would’ve seen continued attrition with non-whites, religious minorities, less affluent people, and so on — even as they continued to build strength with more affluent, educated, more urban and white voters.

In such an alternative world, voters would have explained their electoral choices in terms of other issues that were salient, even though the actual shifts in voting behavior would be relatively consistent with the current 2024 outcomes. I’ve written about this for The Guardian: there are certain patterns of electoral outcomes that seem pretty determined even if the path of how we get there is not. Continued Democratic attrition among working-class, religious, and non-white voters seems to be one of these outcomes that is not dependent upon the features of this particular cycle.

I believe this because the same pattern of attrition has been present in every midterm and general election for more than a decade. In 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020, 2022 and 2024, very different issues were most salient on election day, and very different candidates were competing for power. Yet the same broad trendlines persisted through each. If we want to explain why we see this same pattern across cycles, we cannot plausibly appeal to the unique features of any single election year. Instead, we need a more structural account that patterns across them — a deeper trend that subsumes and informs the others.

My advice to readers for understanding this election, then, would be to take a longer view of how we got here. As alluded to throughout this article, and as comes through clearly in many of the graphics, the attrition Democrats have been seeing with non-white, working class voters and so on — this is not something that just happened in 2024. It’s been going on a while now. These trends helped flip the election in 2016 and, before that, contributed to historic down-ballot wipeouts for the Democratic Party in 2010 through 2014. They continued in 2018-2022, despite some good news for Democrats in each of these cycles, as noted above.

In fact, I’ve basically written this exact same article twice before, in the aftermath of the 2016 and 2020 elections. I produced the same kinds of charts to debunk the same narratives. I illustrated the same trendlines in the demographic constitution of each party’s coalitions.

It is impossible to explain many of these shifts within the dominant narrative frameworks, but people have been loathe to abandon the prevailing narratives, facts be damned. Hence the eternal recurrence of this article, which will continue as long as the underlying facts remain unchanged, and so long as mainstream symbolic capitalists continue to gravitate towards these demonstrably false narratives.

But perhaps this will be the last time I have to write it, after all:

One reason people may be returning to these same self-serving stories is they simply don’t know how else to explain the outcomes. A core element of getting people to abandon false narratives is to provide them with an alternative and better explanation. This is something I haven’t been in a position to do in previous cycles. Now, I certainly can:

One way in which I think (hope) We Have Never Been Woke (and its planned follow up) can help us think about the world is through providing a framework for seeing lots of things that people often discuss separately as part of a deeper story. For instance, there is a lot of talk about the urban/ rural divide in politics, the growing diploma divide, a partisan gender divide, racial dealignment — I think these are all proxies for a more fundamental schism in American society, namely, the divide between symbolic capitalists (and our institutions, communities, etc.) v. those who are more sociologically distant from us. Likewise, the book helps us see how growing inequalities, rising tensions around “identity politics,” the “crisis of expertise,” and the appeal of “populist” leaders like Trump — these are not separate stories either. They’re fronts in a deeper conflict between symbolic capitalists and folks who feel like their values and interests are not represented in our social order (and who often believe that, in fact, symbolic capitalists and aligned institutions are actively hostile towards people like them).

And so, if I was taking a longer view and trying to explain why the election went the way it did, in my opinion, there were two big stories at work:

Ongoing alienation among “normie” Americans from symbolic capitalists, our institutions, our communities, and our preferred political party (the Democrats) – which has been going on for decades, and has analogs in most peer countries as well.

Backlash against the post-2010 “Great Awokening” — including (perhaps especially) among the populations that were supposed to be empowered or represented by these social justice campaigns. As detailed in We Have Never Been Woke, as Awokenings wind down, they are usually followed by right-wing gains at the ballot box. The post-2010 Awokening, now on the downswing, seems to be no exception to the general pattern.

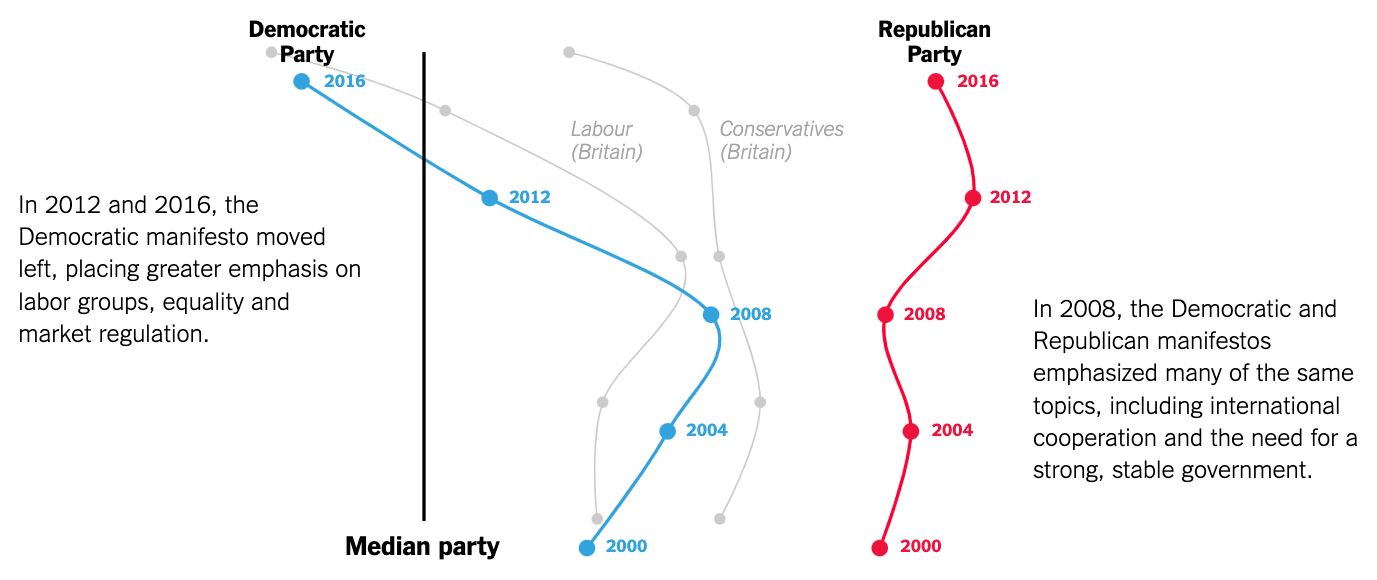

It’s probably not a coincidence that as the Democratic Party platform shifted aggressively after 2008 (even as Republicans moderated under Trump), normie voters started aggressively moving towards the GOP. A single image to help illustrate what happened in recent cycles might be this chart (ignore the spurious vertical line which is based on European parties, with little relevance for U.S. politics):

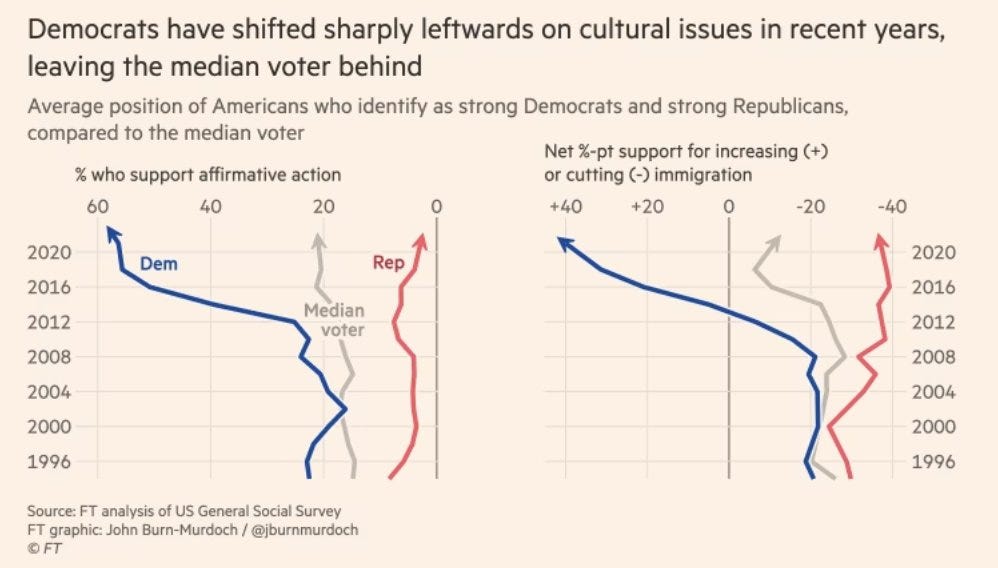

Critically, these changes to the Democratic Party platform didn’t fall out of a coconut tree, they were changes the party made to be responsive to their core constituency, whose views shifted radically during this same period — and in ways that put them at ever greater distance from the median voter, both relative to their past positions, and also relative to their political opponents in the Republican Party, with predictable electoral consequences:

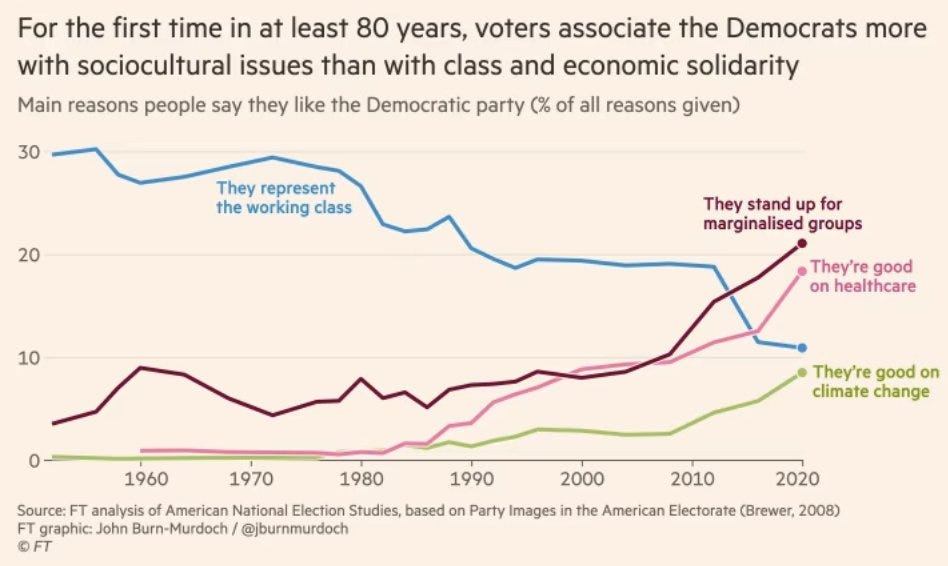

But again, “acute backlash to the post-2010 Great Awokening” is only part of the story. Since the 1970s, when the Democratic Party began reorienting itself around knowledge economy professionals, Americans have grown less and less convinced that the party is concerned about the working class, and increasingly associate the Democrats with sociocultural issues instead:

These two factors — longer-term alienation and acute cultural backlash post-2010 — they don’t just help us understand the top-level outcome of this election (i.e. Democrats lost), they can also contextualize many of the specific shifts observed along the lines of class, race, gender and geography in this cycle and preceding ones. I don’t have space here to unpack this point further (as this essay is already pretty long), so I’d encourage people who want to learn more to check out, We Have Never Been Woke, which develops and substantiates both stories in great detail.

Here I’ll just note that, to the extent that these trends did play a pivotal role in driving the electoral outcome, it would have been an uphill climb to 270 regardless of who the Democrats nominated… unless perhaps they put someone forward who

Promised a major break from Biden and other Democrats on culture issues, and/or

Who vowed more aggressively populist economic policies.

The “symbolically conservative, operationally liberal” quadrant of political views seems to represent a plurality of Americans but has no clear representation among the political parties. If Democrats had moved more aggressively into that quadrant in a way that showed a clear disjunct from the incumbent administration, that could have plausibly helped win over some of the voters who defected or abstained. Research shows that Biden’s economic policies probably did help stem bleeding this cycle: were it not for the more populist posture he took on economics, it would’ve been an even bigger wipeout. A Democrat who went much further in that direction, while achieving significant break from mainstream Democrats on culture issues would probably have been able to win. But shy of that, this race was likely going to be a tough sell even for a compelling and effective mainstream Democratic nominee. Which Harris was not.

Okay, fine, we can talk about this particular campaign now

Given how difficult it is for a party to be oriented around symbolic capitalists while still appealing to sufficient numbers of “normies” to win elections (and in light of the unpopularity of the incumbent regime, which Kamala was a key part of), it was really unfortunate that Harris was the Democrats’ standard bearer for 2024.

Again, she added nothing to the ticket in 2020 in terms of shoring up support from groups where Democrats were seeing losses. Her approval numbers were underwater almost the entire time she was in office as VP and she created a lot of avoidable drama throughout her tenure as well.2 Some urged Biden to drop Kamala and choose an alternative running mate in 2024. It likely would have benefitted the party if he had.

However, to be clear, it would definitely not have helped anything for Biden to have stayed in the race. Although Harris lost decisively, Democrats were headed for a clear landslide defeat with Biden at the top of the ticket – even according to the Biden team’s own internal data. The polling, fundraising, and enthusiasm for the party all shot up durably and dramatically after Biden’s exit – even if the shifts were insufficient to ultimately pull off a win. If anything, Biden should have exited much sooner, allowing Democrats to hold an open primary, and possibly settle around a better alternative candidate.

In any event, Harris was clearly not prepared to succeed Joe Biden when it was her time to shine. Despite the President’s long period of cognitive decline (which she played a key role in covering up), she seemed to have done zero prep work for possibly stepping into the presidency or becoming the nominee. She apparently had no plans or vision to articulate to voters after moving to the top of the ticket. Worse, Kamala largely avoided media for much of her short campaign, rendering it impossible to convey any ideas she did have to voters.

Despite her “turn the page,” rhetoric, Harris was unwilling or unable to distance herself from the unpopular incumbent regime at a time when incumbent parties worldwide were seeing major losses. As in 2016, this was a moment when major change was needed, and Democrats once again ran on preserving the status quo.

This is all just the tip of the iceberg of Kamala’s political malpractice. Ticking through a few major missteps in the final stretch:

Against the advice of her own team, Harris aggressively courted prominent Republican endorsements, and praised people like Alberto Gonzalez and Dick Cheney, who oversaw some of the worst abuses of the post-9/11 era, and campaigned with Liz Cheney. In the process she alienated her own base – and for nothing. Trump saw fewer defections among Republicans and conservatives in 2024 than in previous cycles.

Because Harris was too busy kissing up to Republicans and trying to flip “reach” states rather than securing the “blue wall” in the Rust Belt, she sent NAFTA champion Bill Clinton to Michigan in her stead – a state whose industrial sector was ravaged by Clinton’s own policies. Upon arrival, he spent most of his final pitch to voters lecturing Arabs about why they should be fine with ethnic cleansing in Gaza, while emphasizing that Israel can do as it pleases and U.S. policy wasn’t going to change under Harris, and everyone just needed to make peace with these realities. This was somehow supposed to help win votes in the state! (it didn’t).

Meanwhile, the campaign tried to shore up its weakness with black voters by deploying Barack Obama to patronize and scold folks for being insufficiently warm to Harris. The implicit message was that African Americans somehow owed Harris their vote in virtue of her purported race. In adopting this posture, the “trust the science” party was apparently indifferent to the abundant research showing that attempts to guilt or shame people into political behaviors typically causes backlash instead (i.e. it leads them to behave opposite how you want). No notes.

Finally, in the home stretch, even as the polling tightened, Harris chose to skip one of the most popular podcasts in the world – a program that reaches 11 million people per episode — and at times over 50 million — many of them undecided voters. She skipped this opportunity because she was worried that some members of her staff wouldn’t like it. Not only did she miss a chance to reach a large undecided audience, she gave her opponent uncontested access to that audience (because he did go on the show, as did his VP, each appearance having tens of millions of views) — and ultimately she and her team left such a bad taste in the mouth of her prospective interlocutor that he ended up urging his listeners to vote for her opponent instead. And then, audaciously, after declining to go on the program, progressives responded to Kamala losing by saying they need a Joe Rogan of the left… when they could’ve just gone on the existing Joe Rogan show like they were invited to do! Bernie Sanders did — leading to a Rogan endorsement. But he also got a lot of criticism for it from the scolds Kamala was so afraid of — folks who would apparently rather lose an election that have a conversation with someone “impure.” Rather than being laser-focused on reaching persuadable voters she was worried about impressing these people. In itself, not going on Rogan didn’t cost her the race, but what this episode reveals about her decision making process and top priorities definitely clarifies how she lost so decisively to a deeply unpopular opponent like Trump.

One could go on and on about how Harris took an already-tough situation and made decisions that exacerbated her problems at nearly every turn. But then again, what’d be the point of that? Many Harris sympathizers seem set on believing Kamala’s campaign was “flawless,” and the problem lies with the voters. Because of these same tendencies very little was learned from the previous Trump cycles. I fear the same may hold true this time as well. Distressingly high numbers of influential people seem more interested in telling self-flattering stories than actually winning elections — and it’s hard to persuade folks with that priority set of anything.

But for those who are interested in engaging with empirical evidence, I hope this essay illustrated that many popular talking points about the 2024 election seem to be ill-substantiated. And I hope that I sowed a seed that, if we want to understand not only this election, but previous electoral outcomes and how they relate to one another, it’s important to take a somewhat longer view instead of trying to explain things that are happening today purely in terms of other things happening today. As Jesus put it, “They who have ears, let them hear.”

I did a quick 10 minute talk explaining this problem and walking folks through examples here:

The talk is focused primarily on polarization. However, a similar trend holds for adverse electoral outcomes as well.

In the process of elaborating, let me address one final narrative, namely: Harris made a mistake choosing Tim Walz as her running mate – perhaps she could have pulled off a win if she’d instead gone with Josh Shapiro. Not likely.

First and foremost, Vice Presidential picks don’t tend to shift many votes outside of the candidate’s home state, and often not even there. In this cycle, for instance, Republicans made gains in nearly every single county of Minnesota, despite governor Tim Walz’s presence on the Democratic ticket.

Pennsylvania could have gone the same way with Shapiro as the VP nominee. And, more importantly, even if Democrats had managed to flip the state (worth 19 electoral votes), Harris would have still lost the Electoral College unless having Shapiro would have somehow flipped multiple other states as well (Unlikely. For instance, would Shapiro have helped Democrats in Michigan?).

In fact, there’s a good chance that a Harris/ Shapiro would have led to Pennsylvania voters, and voters more generally, thinking worse of Kamala than they already do. This is because every single campaign and office Harris has presided over has been riven by extreme levels of conflict, drama, turnover, and dysfunction. She ultimately picked Tim Walz because he had no designs on the top job, and stood little chance of usurping the top-of-ticket candidate. Shapiro, meanwhile, purportedly came off as a diva.

Pairing the two of them together would likely have led to many high-profile clashes, staff resignations, and ill-will — as has made its way into public view anytime Harris ran for anything. Even without Shapiro on the ticket, there was deep dysfunction. As one Democratic official put it, “I’m amazed that we even got close. The campaign was broken since the beginning.” With an ambitious and demanding climber like Shapiro trying to put his stamp on the ticket, these problems would have likely been magnified by a lot.

And if Pennsylvania voters perceived deep tension or open conflict between Harris and the popular governor – well, that would haven been unlikely to endear her to voters in the state. Campaign drama would likely have undermined her appeal more broadly as well. All to say, Kamala probably made a good choice in passing over Shapiro in light of the chronic struggles she’s faced with respect to her leadership style.